Recommended

Over the last several weeks of the “Diaries from the Frontline” series, we have shown how COVID-19 and school closures have affected some of the world’s most vulnerable students. Education organizations have had to be adaptive and responsive to meet the most pressing needs of their students and their families while trying to plan for the long-term impacts of the pandemic. In this final blog post of the series, we take a look at the impacts of COVID on the most vulnerable students.

CGD colleagues have written about how school closures are exacerbating inequality, how learning loss will be greater for children with less connectivity and parents less able to help them, and how school closures will put some children at higher risk of violence and other forms of abuse. Girls are more likely to be negatively affected by COVID-19, as 69 percent of education organizations said in response to a CGD survey.

These impacts are likely to continue to be felt in the long term. As evidence from Argentina, the United States, and Indonesia has shown, less educated workers are more affected by economic crises, and students who drop out of school or experience significant declines in learning are likely to face lower lifetime productivity and earnings. That’s in addition to the potential psychological impacts of isolation and in some cases abuse during lockdowns.

This week, we examine how one particularly vulnerable population served by the Luminos Fund—refugee children in Lebanon—has been affected. The Citizens Foundation in Pakistan describes what school closures mean for girls and their education and life opportunities. And Educate Girls, an organization based in India new to the series, shares stories from the frontlines.

Luminos: Education for refugee children during COVID-19

Lebanon is navigating economic strife, inflation, unrest, painful cross-border tension, and a pandemic, all while hosting one of the largest refugee populations in the world per capita. There are 910,256 registered Syrian refugees in Lebanon, but the actual number is likely even higher. Despite the Lebanese government’s efforts to offer school placement to refugee children, over a third of Syrian refugee children in Lebanon at the age of compulsory schooling (6-14) are out of school. For those that are in school, this academic year has had major disruptions: schools closed for weeks in the autumn due to political protests and unrest, and again beginning in March due to COVID.

In Lebanon, the Luminos Fund offers back-to-school and homework support programs for Syrian refugees, including robust psychosocial support such as art and music therapy to help students process trauma. Many students have been out of school for years, and all are learning in English and French (the standard languages of instruction in Lebanon) for the first time. These programs are an opportunity for refugee children to catch up to grade level and prepare to assimilate into Lebanese classrooms. During COVID, Luminos has shifted these programs to online and message-based learning, for example through WhatsApp, which many families identify as their preferred communication format.

For the refugee families that Luminos serves, financial pressure is a greater concern than COVID, which has implications for education. Mahmoud, a father, describes the stress that he feels: “My daughter receives some lessons on WhatsApp, and I go to my neighbor's home to use their internet connection to download the lessons because I do not have enough credits for 3G. Honestly, I am embarrassed because, first, I feel shy when I go to my neighbors’ for internet connection and, second, my financial status is very bad. I am borrowing money to buy food so I don't know how to afford buying my children notebooks, pens, pencils, erasers, etc. I cannot find a job.”

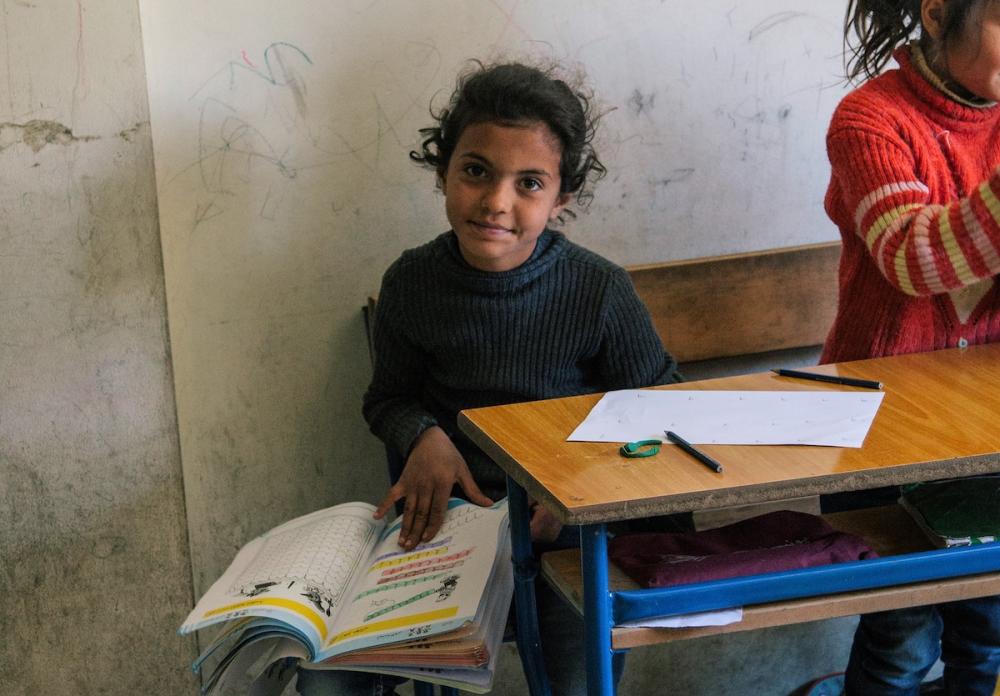

Before the pandemic, a refugee girl studies at a school in Lebanon supported by the Luminos Fund. Photo by Luminos Fund.

Syrian refugee children, both boys and girls, are at particular risk of dropping out of school, especially now. Boys may be needed to earn income for the household. Girls are at risk of early marriage, perhaps to a man with a degree of financial stability, and may be at greater risk of sexual and gender-based violence during the pandemic. Even before COVID, Luminos needed to adjust school hours during harvest season because children go to work, and the crisis is accentuating these hardships.

Some children are studying online, says Assem, a teacher, but adds that he sees children working, like selling napkins at a nearby traffic stop, or playing outdoors during COVID. Families report seeing some children scavenging for food or potential toys.

When the Lebanese-Syrian border reopens, some refugee families may decide to return to Syria, depending on when schools reopen in Lebanon and the family’s assessment of the economic situation—a choice that illuminates the confluence of crises these families face.

Luminos has continued to evaluate new ways to support refugee families and students through the crisis, such as by providing cell data cards to families who will have trouble accessing lessons otherwise. It has considered distributing tablets, but there is concern families may sell these devices for short-term income.

“I hope schools will open and my children return to their schools,” says Azab, a father. “I hope life becomes normal again. I think life will not be normal as it was before because life is financially harder now. Honestly, I don't know what will happen.”

TCF: COVID, gender, and class

“What are we supposed to do with a learning continuity plan when we don’t have anything to eat at home? Our girls are better off stitching footballs, at least that way we can put food on the table,” parents told Shakeela, a TCF principal running a government school for girls in a village in Narowal, Punjab.

TCF estimates that a significant proportion of its students are currently at risk of dropping out, primarily girls and students from the lowest-income families. Boys who come from the lowest socioeconomic backgrounds, especially those currently in secondary school, are also at risk of leaving school to serve as an extra set of hands in the fields or at local shops.

Principals, teachers, and community members from across the TCF network are echoing the challenge of keeping female students in school if closures persist. There’s a particular concern about girls dropping out during the transition from primary to secondary schooling, a problem which predates the pandemic but is likely to be exacerbated in its aftermath. The reasons for this are familiar: the loss of livelihood has a disproportionate impact on girls, as they are expected to take on traditional caregiver roles around the home while their mothers earn a living; distance to school and the cost of transportation; early marriages; and familial and societal pressures.

With several low-cost private schools at risk of closing due to the economic impact of COVID-19, parents are increasingly worried about their daughters’ job prospects (teaching is seen as a safe and respectable job for women, as we noted here). They are calling into question the value of educating them instead of teaching them skills such as beautician work, embroidery, or stitching.

Ahsan, aged 10, used to help his father in the fields after school, but is now working from daybreak to sunset. He says, “Every day we used to play and do activities at school. I miss meeting my teachers and friends. Without school, it’s only work.” For many boys like Ahsan, the transition back to school may be challenging or even impossible, due to the economic pressure his family is facing.

In addition to economic pressures to work, the digital divide is also preventing the continuity of learning for some students who do not have access to technology. That puts kids at greater risk of dropping out, as they’re unable to catch up.

Accounts from the field of the impact of all these factors, however, have been mixed—some TCF principals are confident that they will be able to retain all of their students, while others are much more apprehensive. TCF’s TV program, self-study magazine, and community outreach have sought to keep families and students engaged with education. Continued parental support, where we find it, has been predicated on community members feeling that TCF did not leave them behind: the relief work that TCF has done, coupled with the regular community outreach by phone from principals and teachers has meant that some parents are happy to send their children, daughters and sons alike, back to school. How long this patience will last is yet to be determined.

Educate Girls: Losing girls due to lockdown?

The team at Educate Girls in India recognizes that learning loss due to COVID is important, but has been more troubled by the possibility of scores of girls losing out completely on continuing their education as a result of the pandemic.

They have seen cases of this play out firsthand: Gita, a girl in a remote village in Rajasthan, was on the verge of completing her education when the pandemic hit and her school closed. Gita is a child bride who had been allowed to finish her education before moving in with her husband. Her family deemed it inappropriate for her (as for many girls in the area) to have access to a mobile phone—preventing her from accessing distance learning. When she did briefly use the phone to text a girlfriend, her father and brother believed her to be dishonoring her family, talking to a boy and not her husband, and sent her off to her in-laws earlier than planned. News traveled fast and three other girls in similar situations in Gita’s village were also sent to live with their husbands—accelerating their child marriages and diminishing their futures. They are unlikely now to ever set foot in a classroom again.

Another girl, Pinky, and her three sisters live in fear of their alcoholic father, even without a lockdown and now, cooped up at home, the situation is precarious. The pandemic and lockdown have increased the risks of gender-based violence, with reports of calls to national helplines rapidly increasing. With Educate Girls’ field teams on lockdown, it is hard to translate these stories into quantitative data, but the reports from staff in communities Educate Girls serves have been deeply concerning.

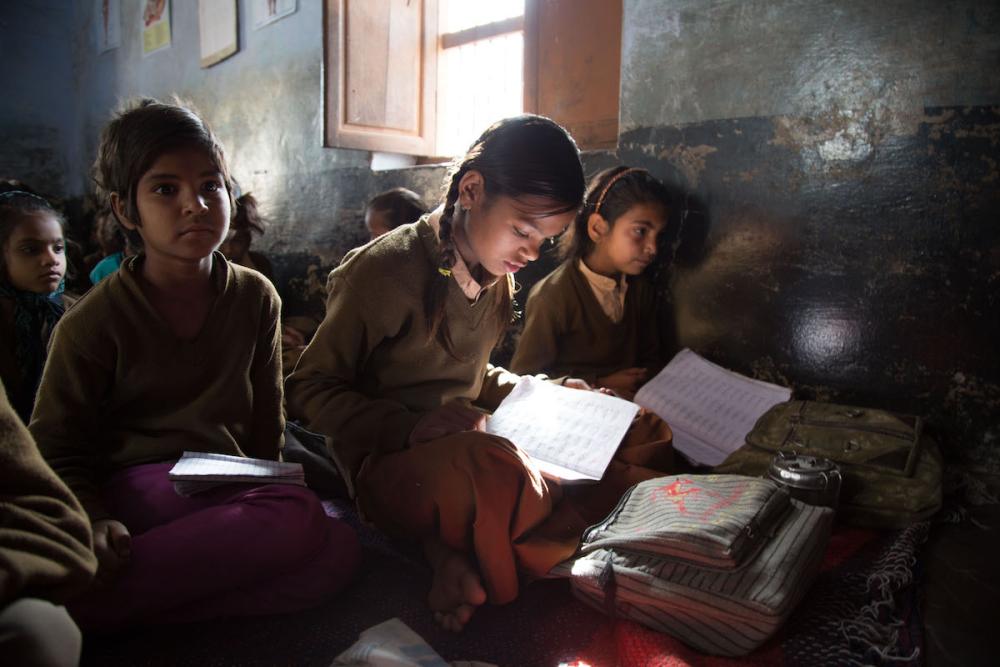

Girls at a school in India served by Educate Girls, before the pandemic and lockdown began. Photo by Educate Girls.

Educate Girls, in partnership with the government of India and local communities, has enrolled more than half a million girls into school over the past 12 years, many for the first time. But the pandemic and lockdowns have created a real fear among staff that more than a decade of progress could disappear overnight. As livelihoods and health issues loom as the greatest risks, education is deprioritized. It is hard for a field worker to pick up the phone and have a conversation about school when their family has lost its income and its food.

Like many other education NGOs, Educate Girls’ staff and volunteers have pivoted to do relief work beyond their usual role, supporting over 100,000 of the worst-hit families across 1,500 villages with the highest concentration of out-of-school girls. Despite substantial fears about the impact of the crisis on girls’ education, the hope is that the crisis will be an opportunity to rethink the systems and policies that have been at the root of girls’ repression all these years—and that NGOs can help press the reset button on the systems that are holding the most vulnerable back.

Thanks very much to the teams at the Luminos Fund, TCF, and Educate Girls for sharing their stories. These stories have illuminated for us what new relief operations, distance learning and learning loss, the roles of educators, and COVID-19 impacts on girls and the most vulnerable populations have meant in reality. While the series is ending for now, CGD’s education team will be continuing to research these issues related to the pandemic’s longer-term effects on global education.

Disclaimer

CGD blog posts reflect the views of the authors, drawing on prior research and experience in their areas of expertise. CGD is a nonpartisan, independent organization and does not take institutional positions.