Along with the agreement on the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) and the Addis Ababa Action Agenda in 2015, the “billions to trillions” vision advanced the notion that some significant part of official development assistance (ODA) should be used to catalyze additional finance from other public and private sources. Seven years later, the expectations that blended finance would expand sharply to help narrow the gaps in financing the SDGs have not been met. Recent data show that the annual blended finance volumes remained relatively constant between 2015 and 2019 around $11 billion, before it experienced a significant drop to $4.5 billion in 2020 in the context of COVID-19.

As part of the 2021 Development Leaders Conference, which CGD co-hosted with the Swedish International Development Agency (Sida) to bring together senior leaders at bilateral aid agencies and multilateral institutions, we undertook a survey of development agencies to understand the current and future use of blended finance in their activities. The 27-question survey was sent to 45 development agencies, 22 of which responded. Nineteen of the respondents are members of the Development Assistance Committee, the club that encompasses the major high-income country donors, and more than half of them (13) are based in Europe. Acknowledging the small sample size of the survey and the necessity to be careful in generalizing the evidence drawn from it, we summarize the main findings of the survey here.

What are the key findings?

Lack of data and targets for blended finance

The survey revealed a scarcity of data on volumes and allocation of finance by country income level and by gender. Twelve of the 22 development agencies (55 percent) lack data on the current share of concessional finance for blending in overall programs; 14 of them (64 percent) could not identify the share of blended finance for low-income countries (LICs, as defined by the World Bank); and 16 of them (73 percent) lack data on the share of blended finance designed to benefit women and girls.

Moreover, many development agencies do not track mobilization of private finance or publish data on blended finance results. Thirteen development agencies (59 percent) reported having no data on the amount of private finance mobilized per dollar of concessional finance in blended operations. Nine agencies (41 percent) do not publish reports on results and impacts of their concessional finance for blending.

When asked about future use of blended finance, many development agencies indicated no plans to set quantitative targets. Thirteen development agencies (59 percent) have not set targets for the future share of concessional finance for blending in overall programs, and 11 agencies (50 percent) have not set targets for the amount of private finance mobilized per dollar of concessional funding used for blending.

A clear focus on sub-Saharan Africa, less so on low-income countries

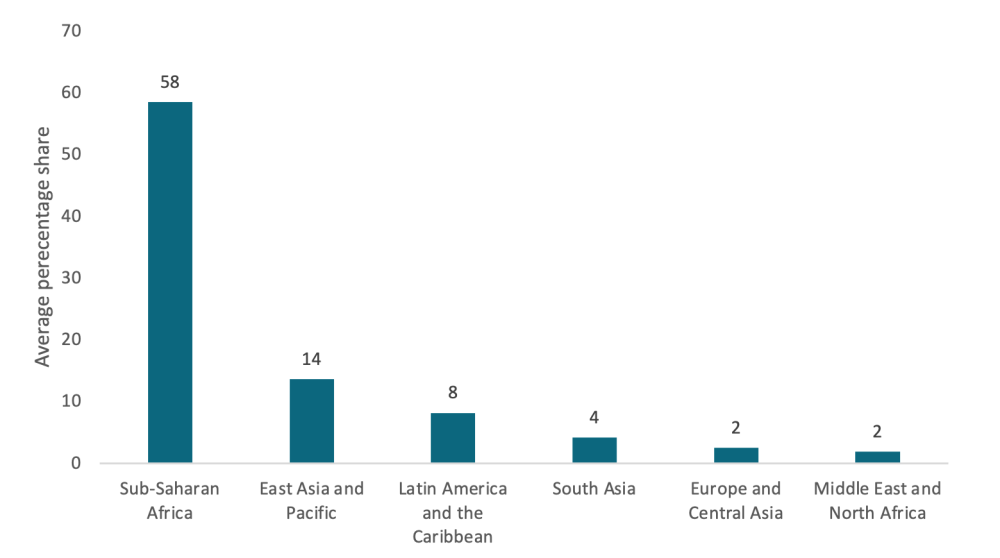

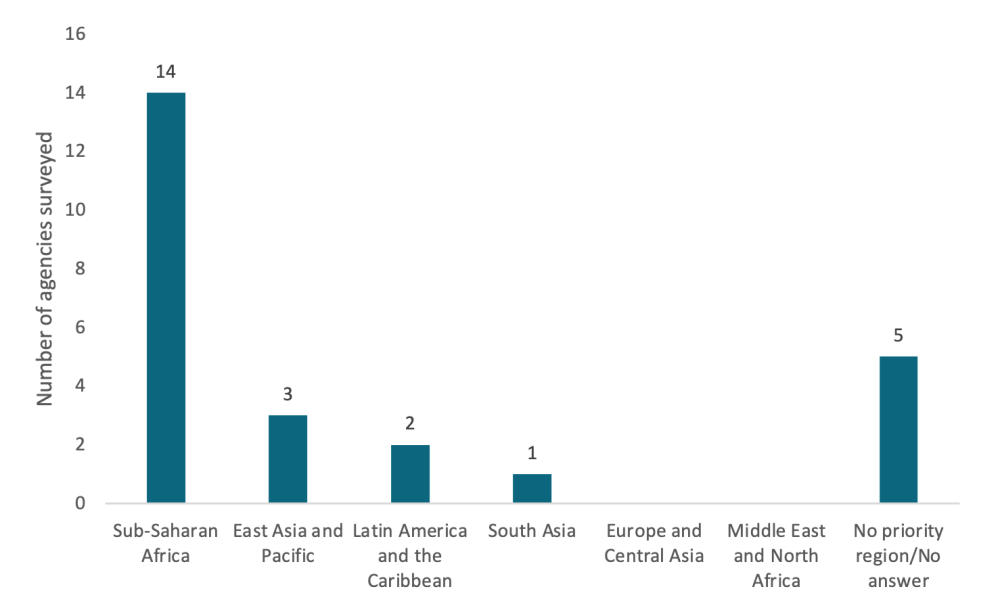

Where respondents do collect data on the geographic distribution of blended finance, there is a clear concentration of activities in sub-Saharan Africa in current and future plans. The average share of blended finance among the respondents in sub-Saharan Africa is 58 percent, while East Asia and the Pacific only represent 14 percent. Moreover, more than half of the agencies (14) are planning to make sub-Saharan Africa a priority region for blended finance operations.

Figure 1. What is the share of blended finance by developing region? (by World Bank-defined regions)

Figure 2. What are the future priority regions for blended finance operations?

However, a focus on sub-Saharan Africa is not necessarily synonymous with a focus on the poorest countries. A majority (14) of respondents currently do not collect data on the share of blended finance in low-income countries (LICs), 19 respondents do not plan to or do not know if they will set a target share for blended finance for LICs.

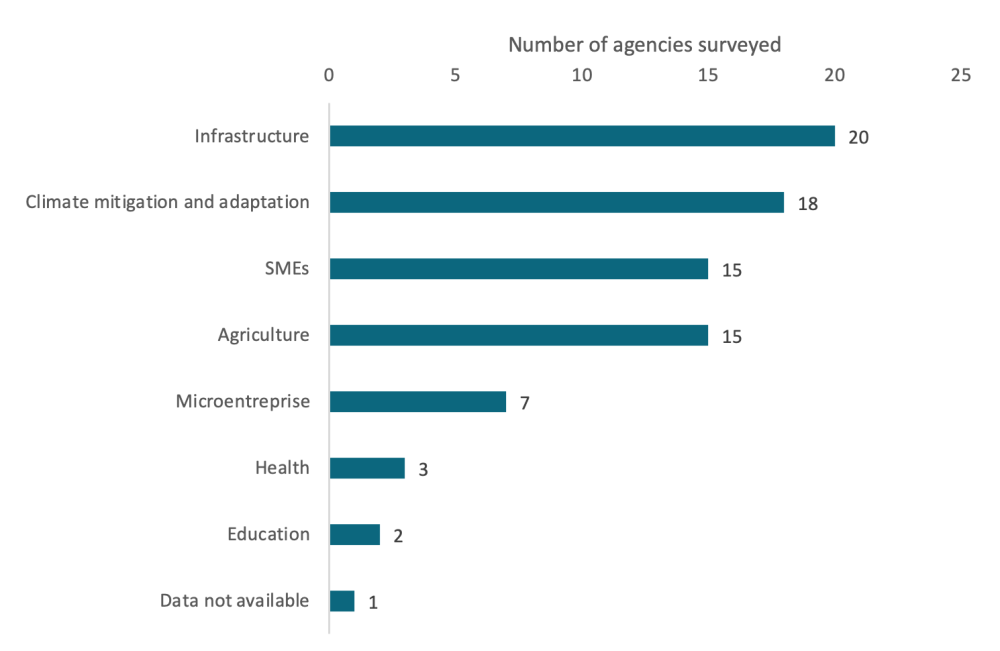

Infrastructure and climate change top the sectoral list

Almost all respondents selected infrastructure (20) and climate mitigation and adaptation (18) as target sectors for blending operations. Other sectors such as small and medium enterprises (15) and agriculture (15) also generated significant interest among respondents. In contrast, social sectors remain underfunded with health and education being the lowest priority for blending operations.

Figure 3. Which are the target (top three) sectors for blended finance operations?

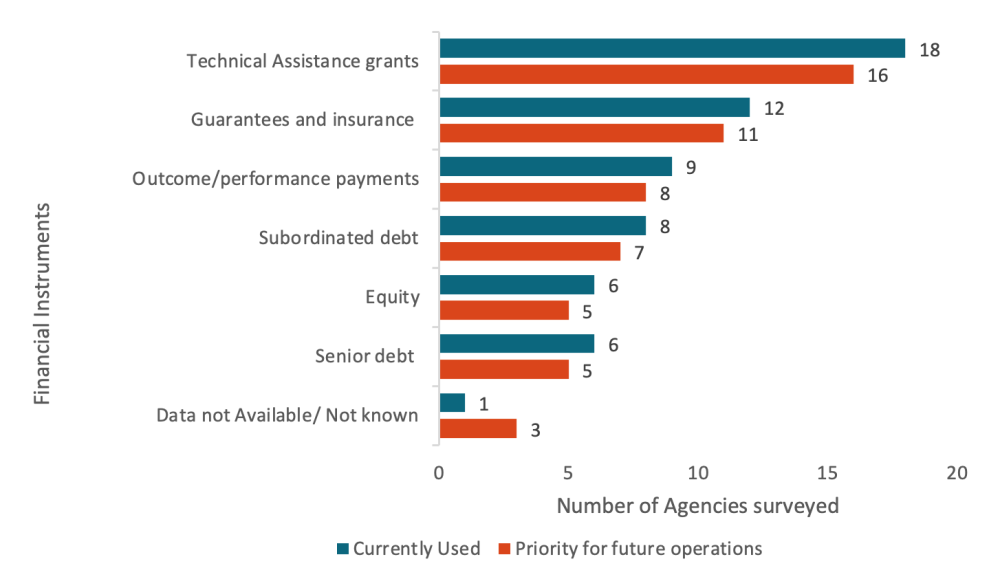

Technical assistance as the preferred instrument

Grants for technical assistance are by far the preferred instrument of development agencies for current and future operations, followed by guarantees and insurance. Agencies also show a relative openness to outcome and performance payments, which could be a powerful tool for incentivizing private investment on the revenue side, rather than reducing costs and risks.

Figure 4. What financial instruments are and will be used in blended finance operations?

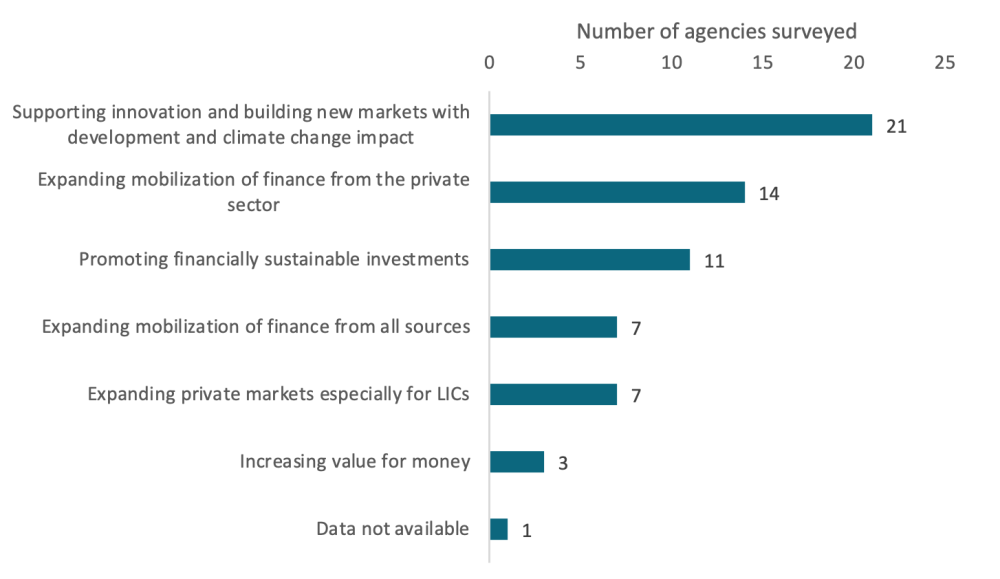

It is significant that almost all agencies (95 percent), use blended finance to support innovation and build new markets. This suggests a welcome focus on using blended finance for broader spillover benefits beyond individual transactions to larger market development.

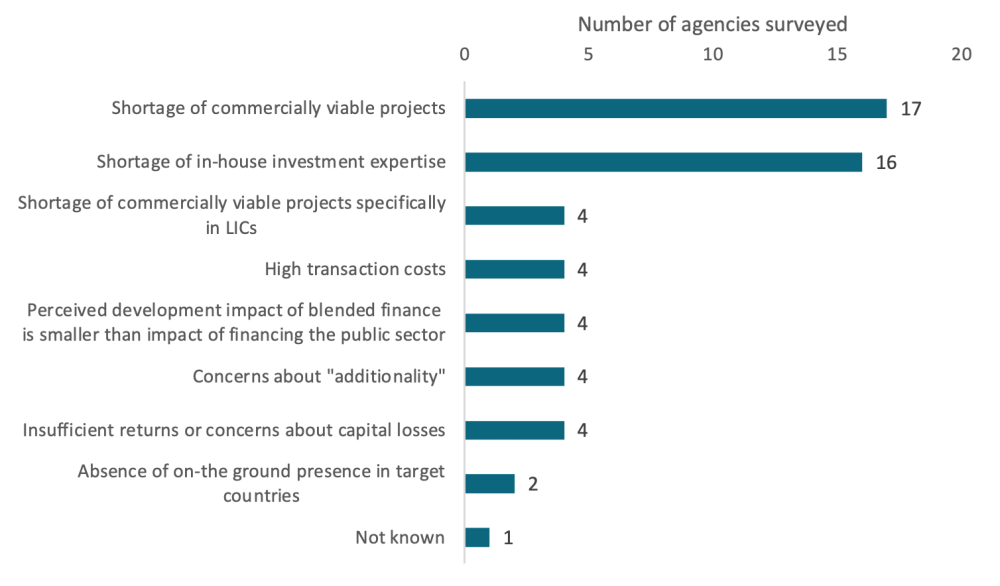

Most development agencies identified the lack of commercially viable projects (77 percent) and the shortage of in-house expertise (72 percent) as the main obstacles to the provision of blended finance. Surprisingly, expanding mobilization of finance from all sources was not seen as a primary objective of blended finance activities (only 7 agencies, or 31 percent, selected that response). Similarly, transaction costs or concerns about capital losses were not considered to be the main obstacles.

Figure 5. What are the principal (top three) objectives of blended finance activities?

Figure 6. What are the biggest (top three) obstacles to expansion of blended finance activities?

Openness to partnerships

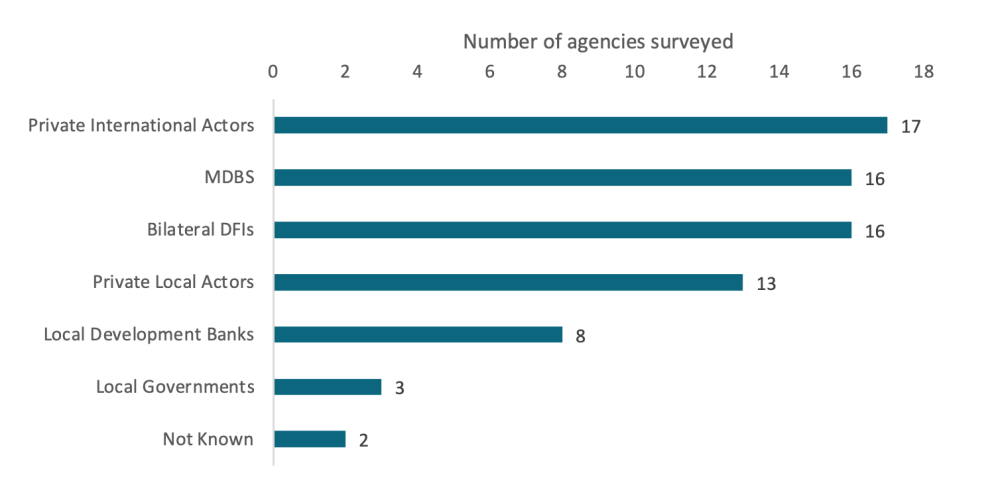

Agencies see partnerships as being key to expand the use of blended finance. They are open to partnering with a wide range of actors, private and public at the international and country level. Preferred partners are private international actors (77 percent) and multilateral development banks and bilateral development finance institutions (72 percent), whereas the local development banks and governments rank the lowest (36 percent and 13 percent, respectively). The relatively low interest in partnering with local official partners may indicate a preference for engaging with these partners through traditional aid, rather than blended finance. A little over half (59 percent) of aid agencies also want to build in-house capacity.

Figure 7. Which will be the preferred (top three) private and public partners for blended finance operations?

Conclusions

The survey reveals relatively few aid agency action plans, commitments, or targets for expanding blended finance. These findings are surprising given the growing understanding of the critical role the private sector must play in helping to fill SDG finance gaps.

Aid agencies have the scarcest form of development finance—risk-tolerant finance—exactly the kind that has the most catalytic potential. They have other advantages as well. Many have the on-the-ground presence needed to engage with local private actors for finding and building projects. And they have the strong relationships with governments needed to support the policies and institutions that will make more projects bankable.

A welcome survey finding is that aid agencies are thinking about the systemic impact of their blended finance activities. They want to use blended finance on transactions that will have broader innovation and market benefits. And there is a clear understanding that they need to form partnerships and build in-house capacity in order to expand their blended finance operations.

But without well-considered, well-defined strategies and targets for the growth and allocation of blended finance, aid agencies, which control most concessional finance that comes from outside developing countries, will not make their essential contribution to scaling both blended finance and mobilization of private finance for SDGs. This survey reveals that they have a long way to go. And the urgency of using some larger portion of aid dollars more catalytically has only increased as finance gaps are widened by the pandemic and accelerating climate change.

Disclaimer

CGD blog posts reflect the views of the authors, drawing on prior research and experience in their areas of expertise. CGD is a nonpartisan, independent organization and does not take institutional positions.