Recommended

In a new policy paper published today, we set out the case for using pull financing to solve problems that affect both development and climate outcomes by incentivising transformational change through technical innovation or massive-scale production and distribution of existing technologies. Pull financing is risky, but it sets out to achieve something that the market won’t achieve and conventional financing finds it hard to achieve, with potentially large returns, as we set out in a previous paper. Solving problems like crop residue burning requires either new technologies or dramatically less costly ways of applying existing ones, but the payoff in terms of carbon emissions and local health benefits are potentially enormous. Developing new crop varieties robust to coming climatic changes, and rolling them out at a scale capable of transforming agricultural productivity in Africa, requires both innovation and careful attention to the challenges of take-up, but a green revolution for climate change is a prize worth taking risks for. Neither of these problems will be solved by the market alone: there simply aren’t enough buyers willing to pay enough to make it worthwhile for private innovators and producers to invest in solving these problems now, at scale. A helping hand is needed.

However, one big question our paper leaves unaddressed is how to manage such an ambitious programme of work. In this blog we set out what an institutional structure capable of managing a diverse portfolio of pull financing activities would look like, and end with an open question: which—if any—current organizations is closest to being able to meeting the criteria we set out?

Challenges of a pull financing mechanism

There are two main challenges that an institution managing a portfolio of pull financing mechanisms must solve to be successful. The first challenge is to identify and specify the problems it seeks to solve, and monitor and assess the proposed solutions. Existing research may set out promising areas, the costs and benefits of addressing them, and even the broad contracting structure required. Still, any institution managing a pull financing mechanism needs access to technical experts able to assess whether a problem has been solved (and hence whether to pay out on the contract) and the characteristics of that solution (for example, is it permanent and self-sustaining? Does it require repeated rounds of treatment? Are the effects consistent across settings and time?)This requires problem-specific technical expertise.

The second, and fundamental, challenge is contracting. Because pull financing mechanisms do not pay for inputs or outputs that already exist and are well-understood (such as time spent on a project or units of a product that already exists and for which production capacity and a unit cost is well known), but instead pays for desired outcomes which no existing process or structure currently produces, it is more prone to unintended consequences or paying for the wrong thing. If we are simply buying 1 million bed nets for example, we can examine existing bed nets that have been successfully deployed and write a contract that specifies that the bed nets delivered must meet the specifications of the ones we examined. If, on the other hand, we want to buy 1 million units of a yet-to-be-developed technology, say a new system for repelling mosquitos, we are forced to imagine what the product will be. More accurately, we are forced to specify the essential characteristics of the product to be delivered, and leave the rest unspecified. This is both difficult, because identifying the essential characteristics of a product before it exists can be challenging and because what is unspecified may turn out to be important in ways we cannot predict. Even if we want to purchase an existing product, but at a scale far beyond what production capacity today can offer, we need to predict what the right per-unit cost to pay is. That, too, is difficult, because it forces us to imagine what how the cost of production evolves with scale, which is not obvious to outsiders to the production process. This requires general contracting expertise.

These two key challenges are quite different and requires an institutional set-up with a very specific set of capabilities, or access to them. Pull financing applications also present particularly tricky forms of each challenge, requiring high-quality staff (though not necessarily a very large permanent staffing presence). We suggest how an institutional form capable of delivering both to the standard required and ask: do we need to build it from scratch?

An ideal institutional form

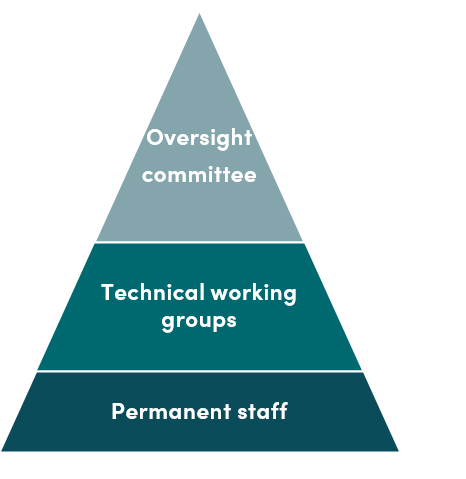

One of the key difficulties of creating an institution capable of meeting both key challenges across a range of pull mechanisms is that they require deep expertise on a wide range of sometimes unconnected issues. We propose a three-tiered pyramidical structure, each with a specific role and personnel:

- At the base of the pyramid, a permanent staff, responsible for setting the broad strategic direction of the portfolio (including selecting short lists of potential applications); back office functions including financial management, project management and recruitment; and routine reporting to donors, analysis of activities and horizon scanning for new applications and opportunities.

- At the top of the pyramid, an oversight committee made up of eminent economists, climate and environmental scientists, and contracting specialists. The function of this committee would be to offer broad high-level advice, sign off and agree on the strategic direction, portfolio construction choices, specific financial commitments, and contracting choices. The committee should not (with the exception, perhaps of a CEO) be permanently employed. Rather, it should function more like a team of non-executive directors, meeting occasionally to provide expert strategic advice. To maximise the chances of attracting the very best people in each relevant field, the time requirements of this committee should be kept as low as possible.

- In between these layers, a series of technical working groups managing each application consisting of some full- and some part-time staff on fixed-term or consultancy contracts. These working groups would consist of economists, technical specialists selected according to the application, and contracting specialists. These working groups would make the detailed decisions on how to structure and manage each of the specific pull mechanisms that the institution funds. Their size could vary, according to the workload: over time, even while the mechanism is active, there will be less need for standing capacity in the working groups. Technical groups and permanent staff should include specific local expertise from the countries in which each mechanism is expected to operate so local conditions—in all respects: economic, legal, and environmental—are adequately considered in the design of each mechanism.

This structure, while complex, aims at accessing the best possible expertise without astronomical staffing costs. Though both the oversight committee and technical working groups would involve high per-day or per-person costs, they are structured to operate by paying for top-quality expertise for short periods of time, rather than maintaining a larger full-time staff permanently. The flip side to this is that it will also pay for a top-quality back office and small but highly competent permanent staff. Making ambitious pull financing projects work is risky and difficult; but if donors are willing to spend in the hundreds of millions of dollars to achieve outsize gains, they should be willing to pay for the staff to maximise the chances of success.

Finding the appropriate institutional form

The institutional form set out above is ambitious, but would likely in the end be of modest size. It could plausibly be set up in one of three ways:

- House it in an existing institution. For example, it could be set up as part of the Global Innovation Fund (GIF), which could simply establish a new directorate dedicated to administering the pull financing mechanism. The GIF has the convening power to access top-level experts to form an oversight committee, but would need to substantially adapt its operating model to accommodate the needs of a pull portfolio.

- House it in a smaller, arms-length body that reports to an existing organization. Depending on its size and complexity, a pull financing portfolio could simply be managed through a World Bank Trust Fund, drawing on the convening power of the bank to form an oversight committee, and the global network of technical experts the bank and the fund have access to for the technical working groups. The World Bank has the experience of working on such issues, and manages several billion dollars of resources in trusts already.

- Create a special-purpose vehicle funded by donors. If neither of these options is feasible, donors can set aside funding for establishing an entirely new institution with a staffing and mandate explicitly designed for its purpose. This would, of course, allow for as much tailoring and tinkering with institutional form as required, but comes with two main drawbacks. An entirely new institution may not have the convening power or networks to adequately staff the oversight committee or the technical working groups. And it would be much more expensive and complicated, at least early on.

If at all possible, we recommend one of the first two options. Creating an entirely new organization brings with it an entirely separate set of challenges and difficulties and only increases the risks associated with developing a pull financing portfolio. Using an existing institution, either directly or as an a parent body, eases and shortens the path towards implementation of the first pull mechanisms. But this leaves the question of which institution to use?

Who should do it?

We have mentioned only two institutions by name here, the GIF and World Bank, and for good reason. We want to hear from readers about which other existing organizations have the convening power to create an oversight committee of sufficient quality and standing; access to a network of technical experts required for the creation of a broad range of technical working groups; and the expertise or ability to recruit expertise for a small permanent staff with climate, development, and contracting skills. Who have we missed? Please either comment here or email us at rdissanayake@cgdev.org and badrogue@cgdev.org.

Disclaimer

CGD blog posts reflect the views of the authors, drawing on prior research and experience in their areas of expertise. CGD is a nonpartisan, independent organization and does not take institutional positions.