Recommended

The UK government has recently ramped up the amount of aid that is directed towards research and development. As we have written elsewhere, this could be a good use of official development assistance (ODA), but only if it is spent well: on pressing development issues. This should not be seen as an opportunity to plug university funding deficits in the UK, to circumvent the strict scrutiny and transparency placed on ODA channeled through DFID, or to provide unrivalled material benefit to British institutions which would then make this “tied” aid. This blog post focuses on a proportion of UK research ODA that we believe does not clear this bar.

We demonstrate that some aid is given unrestricted to English Universities, according to a formula that allocates research funds in the national interest, with no reference to development achievement or expertise. Given that the formula only takes English Universities into account, it should also clearly be considered as tied aid—foreign aid that must be spent in the donor country—as it provides direct benefits to British institutions with no international competition. We recommend that either the allocation of this aid take into account development expertise and is genuinely open to universities globally (especially those in developing countries), or it is abolished.

Structure of research funding in the UK

The funding for ODA-eligible research in the UK is structured in a very similar way to the rest of government spending on research, which has three components:

-

Government departmental research spending: The purpose of this funding is to ensure that departments like DFID and the Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs (DEFRA) have the resources to investigate matters of practical relevance to their function; departments can commission research on the best way to achieve their goals, or perform evaluations of existing programmes.

-

Research council directed funding: Research councils in the UK disburse funding for thematic research (e.g., the Economic and Social Research Council funds social science research) to UK universities. Disbursements are largely driven by funding calls, but researchers can also apply directly (in particular early-stage researchers such as PhD students).

-

“Quality related” (QR) research funding: This funding is allocated on the basis of the quality of past research, as well as the expected costs of different research programmes. Research England (previously the Higher Education Funding Council for England), the body with oversight of the council, conducts assessments and disburses funds according to a formula that takes into account these variables. Relatively little accountability for this funding is required—it is essentially core funding for universities.

This funding model makes a lot of sense for general research spending. Departments have budgets to commission research directly relevant to their goals, and research councils have some power to direct funding to broad research agendas that the government has prioritised (both by setting the structure of the councils and directing funding calls therein). But there is also a remaining component of unrestricted funding that can help foster universities as centres of research excellence, and help to maintain the UK’s reputation as a prestigious place to study and conduct research.

As universities increasingly receive ODA funds, how well does this model translate to allocations of ODA? Departmental research spending that is classed as ODA is primarily funded by DFID, who generally spend it on evaluations of programmes, and on gathering evidence for the best ways of spending aid. The ODA directed through research councils is generally in the form of funding calls formed by researchers in conjunction with development experts (overseen by the “Strategic Coherence of ODA Research” board), and so at least has the potential to be demand-led and focused on real development needs.

However, this development focus is less clear with “quality-related” research funding, which in the case of ODA comes mainly from the Global Challenges Research Fund (GCRF), a pot of research-dedicated funding all classed as ODA. While this is the smallest component of R&D ODA, it still amounted to around £60 million in 2018.

For general (non-ODA) funding, the purpose of the QR research component is to give universities “a degree of research stability and independence not provided by other funding sources.” It ensures that universities remain centres of research excellence by providing them with the flexibility to respond to emerging needs. It also provides stability given that reassessments are infrequent, meaning that universities can be sure to receive a set amount of funding over a longer period. These are laudable aims for national allocation of research funds, but are they compatible with a reasonable allocation of ODA?

How is QR ODA allocated?

In previous years, there were no accountability mechanisms in place to ensure this funding was used for ODA purposes (in short, where overseas development is the main objective). The Higher Education Funding Council for England (HEFCE) and the Department for Business, Energy, Innovation and Skills (BEIS) agreed that the GCRF QR funds would be disbursed in proportion to overall QR funding. After a critical review of this funding process from the Independent Commission for Aid Impact (ICAI), the UK’s aid watchdog, it was accepted that this was “not judged sufficient to meet the ODA reporting standards.” A survey of universities in receipt of this funding found that most could not account for how it was spent, and therefore whether it was spent on development, suggesting that “targeted development assistance” was not its principle aim.

New reporting requirements: better late than never

In response, Research England decided to introduce additional safeguards. In order to be eligible for GCRF QR funding, universities are required to write a strategy outlining how their use of the funds will be ODA compatible, and how it fits within the broader strategic goals of GRCF. In theory this ensures that universities have thought about how they can contribute to poverty reduction. It gives Research England grounds on which to monitor the spending and ensure that the strategy is followed, and that it is ODA compliant.

In practice, it doesn’t seem to be a high bar. Out of 122 universities, 107 submitted strategies requesting QR funding from the GCRF, and every single one received funding. No university was turned down for QR funding on the basis that their strategy was not ODA compliant, or that it didn’t seem sufficiently focused on GCRF goals.

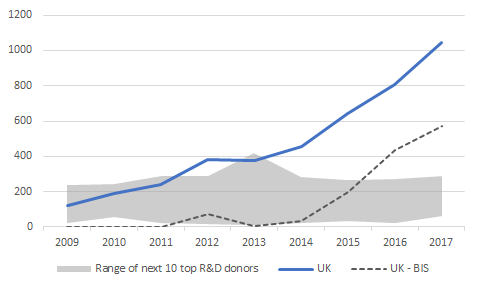

However, Research England could have taken the strategies into account in allocating the level of funding. They provide a list of 10 strategies that they have “commended,” for both their “full embrace of ODA principles” and for how development-related research has been embedded within a broader strategy. Given that these strategies differ in their alignment with ODA principles, Research England could have used this variation to inform their funding allocation. But it didn’t. Research England are clear that the QR funding is still allocated “in proportion with general QR funding,” i.e., proportional to funding allocated according to national priorities only. Figure 1 bears this out, by plotting the total funding received from Research England against the QR ODA research received from GCRF. The correlation is nearly one, implying that QR ODA is allocated in exactly the same way as other QR funding. In other words, the quality of the strategy doesn’t matter for how ODA funding is allocated.

Figure 1. Non-ODA and ODA Quality-Related Funding, 2018

Although the necessity of submitting a strategy appears to be a tick-box exercise, Research England has also introduced another safeguard: the QR spending will be subject to annual monitoring from 2018/19 onwards, to ensure funds are being spent in an ODA-compliant way. Universities will have to provide a breakdown of the spending of their QR funding from GCRF, including types of activity funded and the developing countries involved. Perhaps this will ensure that if universities are not equally able to demonstrate how the funding is contributing to ODA goals, some funding will be suspended.

However, the evidence so far is not promising. Although the annual monitoring process had not yet been established, in 2017, universities were asked to provide Research England’s predecessor (HEFCE) with “case studies” demonstrating that funds had been spent in accordance with ODA principles. There is no indication that the QR allocation from GCRF was changed in light of this monitoring: the 2018 QR funding allocation from GCRF was perfectly correlated with the overall QR funding in 2016. According to Research England, this also means it was perfectly correlated with the GCRF QR funding that year, although the actual data doesn’t seem to be available. Perhaps they all passed this monitoring exercise with flying colours, and all case studies were equally helpful for development, but it seems unlikely that this would be the case for all 107 universities.

Tied aid?

Finally, only UK universities are eligible to apply for this stream of funding—clearly tied aid. Research and Development may not be included under the “OECD Recommendation on Tied Aid”, but nevertheless, the UK reports that 100 percent of its aid is untied. That is inaccurate. If this aid is going to the best places to conduct the research it is funding, then that is only by coincidence. The UK does not have a monopoly on research excellence, and universities in developing countries might be better placed to answer local development questions. Even aside from the question of whether the aid is tied, given that QR ODA funding is simply allocated in proportion to overall QR funding, it is likely that the aid could be better distributed within the UK university system. But given there are many other universities and research institutes worldwide that also study development topics, it is likely a considerable amount of that aid could be better spent outside the UK university system.

While it may be convenient to transfer the funding model directly from domestic research to aid-funded research, this is unlikely to guarantee that aid is as well spent as possible. Although additional reporting requirements have been introduced since the critical ICAI report, these appear to have no bite, having not affected funding allocations and are therefore a waste of resources themselves.

Core-funding is not necessarily wrong, if it can be shown to be spent on ODA-eligible purposes (although it may make it difficult to ensure all ODA is allocated strategically). But a formula that was developed to allocate funding in the national interest is not the right formula to allocate funding geared towards development assistance. If the government is to continue to allocate funding according to the quality of research, then this should be the quality of development research.

If QR funding is to remain, the government should use a different formula when it is ODA funded. Expertise of researchers is important, but only if it is relevant to development. And unlike the standard QR formula, there is no reason to limit allocations to UK universities. If development is the main priority—as it must be for the funding to be classed as ODA—then it doesn’t matter whether it is Oxford, Harvard, or Ibadan that benefits. Not only that, but the formula should give additional weight to developing country universities, where benefits extend beyond the research conducted, such as building capacity and supporting skilled employment. As CGD colleagues have pointed out, providing more unrestricted funding to universities in Africa could help them to develop their own research agendas based on local expertise. Whereas the current formula has a “London weighting”—and so provides more funding to London universities—a better formula for ODA funded research would have a “developing country weighting.”

If the government is unwilling to allocate ODA-funded QR funding in a way that rewards development expertise, and is genuinely untied, then it should abolish it.

This blog post was written and researched by Euan Ritchie. Many thanks to Charles Kenny for helpful suggestions, and to Ian Mitchell for helpful suggestions on an earlier draft.

Disclaimer

CGD blog posts reflect the views of the authors, drawing on prior research and experience in their areas of expertise. CGD is a nonpartisan, independent organization and does not take institutional positions.