Recommended

Introduction

Next week, Women Deliver—the world’s largest conference on gender equality and the health, rights, and wellbeing of women and girls—will kick off. At just around 200 days before the calendar turns to 2020, this conference is an opportunity for the family planning (FP) community—including the FP2020 Core Partners (the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, DFID, UNFPA, and USAID) and Reference Group—to review lessons from the past eight years and look forward beyond 2020, the landmark that has long dominated FP discussions. The key question: In a rapidly changing context, how can the FP community sustain gains and realize the benefits of high-quality FP access in low- and middle-income countries, including lower maternal mortality, better newborn and child health, and increased women’s empowerment?[1]

This note highlights three issues for the global FP movement post-2020, building on CGD’s engagement in this space, including our working group on alignment in family planning.[2] We review the underlying critical assumptions in FP2020’s initial design along with their strengths and weaknesses, and place future approaches squarely within the context of today’s evolving landscape—one that looks very different than the year 2012, when FP2020 was launched.

Flashback to 2012: The Past as Prologue

Family Planning 2020 (FP2020) was launched at the London Summit in July 2012 with much fanfare. It was an ambitious plan with an aspirational goal—120 million additional users of voluntary, high-quality FP services by 2020. And indeed, the FP2020 collective of country governments and donor partners has been part of the global effort to expand FP access in 69 of the world’s poorest countries; compared to 2012, 46 million additional women and girls are using modern contraception.[3] Further, FP2020 and its partners have expanded data collection and analysis. Shared learning and collective action have also been realized through regional engagements like the Ouagadougou Partnership. The Partnership exceeded its initial goal of supporting one million additional users, an increase of over 30 percent, through a coordinated plan to address national laws and regulations, mapping of needs to the local level, programming through high-impact practices (HIPS), and increased funding.[4]

Nearly a decade later, it is a good time to reflect on past lessons and constructively plan for what comes next. At a time when many FP2020 countries are experiencing large increases in the number of people entering reproductive age, expanding access to quality FP services is more important than ever for women, families, communities, and nations as they strive to attain both health and development goals.

In comparison to 2012, when funding was growing, today’s world is one of stagnant donor funding even while multiple global health entities seek replenishments.[5] Adding to this complexity is the changing donor policy environment and evolving donor strategies focused on transition away from aid, including USAID’s journey to self-reliance approach.[6] In tandem, global momentum toward universal health coverage (UHC) has elevated holistic approaches to health financing—potentially replacing the vertical organization by condition- or intervention-specific programs, including those for family planning. Within many countries, there is also a strong movement to decentralize decision making to subnational entities. Finally, the introduction and evolution of a new multilateral funding institution—the Global Financing Facility (GFF)—adds yet another dimension of complexity.

The initial strategy and design of the FP2020 Partnership was built upon a theory of change that reflected the 2012 environment and is no longer fit for purpose. Specifically, we identify and examine with hindsight three assumptions that underpinned FP2020’s strategy in 2012:

-

More donor and domestic money for FP would be forthcoming;

-

A coordinated partnership would enhance accountability for progress; and

-

Harmonizing and aligning FP efforts would achieve greater efficiencies.

In the next section, we review these three assumptions as experienced since 2012, including the strengths, limitations, learnings, and future opportunities. Our analysis leads us to three big-picture takeaways that can help guide the next phase of international FP action: (1) a new paradigm of resource mobilization is needed; (2) accountability requires a clear mandate; accountability and advocacy may not mix; and (3) time to align behind an integrated health financing approach, while keeping the focus on accountability?

We look forward to learning the outcomes of the valuable exchanges planned for Women Deliver and how CGD can contribute to these ongoing discussions to define the post-2020 FP landscape. The clock is ticking.

Critical 2012 Assumptions and Key Takeaways for Post-2020

Assumption 1: More donor and domestic money for FP would be forthcoming

Defining a common, easy-to-communicate goal and then encouraging tangible commitments against that goal was a central tenet of FP2020’s theory of change. Two major goals were defined: a program goal and a financing goal.

First, the FP2020 partnership defined an ambitious programmatic goal to reach 120 million additional users of modern contraception in 69 focus countries by 2020. The headline goal aimed to align the FP community behind a shared ambition and provide a single rallying call to advocate for additional financial contributions. In turn, the community also set an aspirational financial goal of $4.6 billion in additional funding, including $2.6 billion from international donors and the private sector. In doing so, the FP2020 partners believed that FP funding flows would increase dramatically if FP’s central role in both individual and national goals could be successfully highlighted, transparently costed, and politically prioritized.

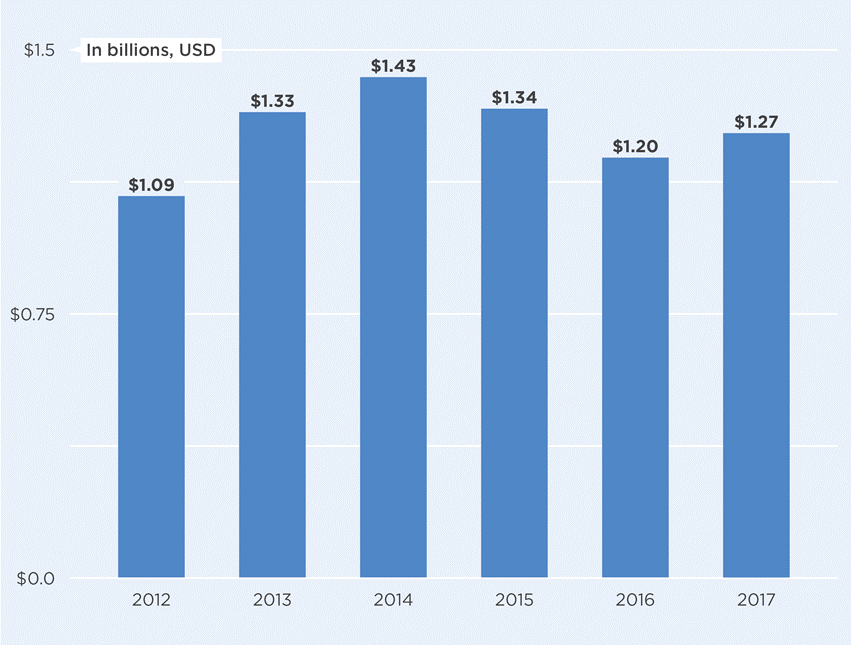

Contrary to expectations, however, large increases in bilateral donor funds have not been realized. Bilateral donor funding for FP increased in the immediate aftermath of 2012, but since 2014 has flatlined or declined (see Figure 1).[7] There are several reasons for this outcome. The vast majority of international FP assistance comes from just five bilateral donors—in 2017, the US, UK, Netherlands, Sweden, and Canada accounted for 90 percent of donor government funding for FP—many of whom have seen foreign aid budgets flatline or decrease among recent political shifts toward populism, especially in the US and across Europe. Even with the welcome new commitments announced in 2018 by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, DFID, and Canada, FP donor funding appears now to be flatlining at best.[8] Further, while many of the new donor commitments for FP support FP2020 through advocacy, data collection, and accountability mechanisms—along with continued investment on longer term goals, such as developing new FP methods—a major portion of the new investments do not appear to be for direct service delivery.

Figure 1. International Bilateral FP Assistance from Donor Governments: Disbursements 2012-2017

Figures based on Kaiser Family Foundation analysis of donor government funding for family planning.

FP2020 had encouraged countries to put together costed implementation plans to expand FP access, implying that donors would increase their bilateral contributions to help fill estimated gaps. Yet in this relatively stagnant overall funding environment, most focus countries did not see an influx of new external fiscal resources materialize.

FP2020 also sought to increase domestic resources for FP, which has proved exceptionally difficult to document, due in large part to the integrated nature of the budgeting approach in most countries. In 2012, FP2020 welcomed its first country commitments; since then the number of public commitments increased rapidly.[9] FP2020 has, in turn, directed considerable effort to the documentation of FP-specific domestic resource expenditures, and for the first time in 2018, reported validated data for 31 countries (see indicator 12).[10] The difficulty in gathering this data is highlighted by the fact that the estimates are from four different sources, each using distinct methodologies and covering different years ranging from 2011–2016.

Notwithstanding these data collection challenges, it is clear that domestic resource mobilization has been more difficult than anticipated. Though the estimates are imprecise, and though some focus countries directly finance large portions of their overall FP programs, most countries did not increase domestic financing for FP in any significant way. Mobilizing domestic resources for FP has been more complicated than anticipated; most countries have limited fiscal space for additional health spending, many are facing transition or increased co-financing requirements from one or more sources of donor health aid (e.g., Gavi, Global Fund, etc.), and FP donors have yet to introduce co-financing requirements or other programs to incentivize domestic expenditure.[11]

All told, significantly greater financial resources for FP programs did not materialize. However, FP resources did not decline from 2012 levels despite an increasingly hostile political environment.[12] In addition, FP2020’s work to build political will and induce policy commitments to FP scale-up may have been important in other ways. For example, political voice reinforces the government’s commitment to FP, decreasing possible cultural opposition, highlighting the central role of FP contributions across health and development, thus clearly signaling that domestic investment is important. Further, better understanding of domestic spending on FP, health, and related sectors may help enhance transparency of decision making and allow increased accountability by defining funding flows in the context of anticipated outputs and outcomes.[13]

Key takeaway 1: A new paradigm of resource mobilization is needed

Traditional donors are feeling the fiscal squeeze, while national governments face competing priorities for the use of scarce public monies both within and outside the health sector. In today’s context, compelling advocacy alone cannot be expected to mobilize additional resources—a new paradigm is needed. The constrained fiscal space for dramatic increases in FP and health spending reinforces the importance of adopting multiple approaches—which have been limited to date—including improved macroeconomic conditions, generation of increased revenues by raising taxes on tobacco and alcohol, prioritization of health within government budgets, and improved efficiencies within the health sector.[14] New donors like high-net-worth individuals and philanthropic networks could also play a role in leveraging additional resources.[15]

Further, the current paradigm shift towards integrated planning and financing of UHC across the health sector suggests the possibility of harnessing FP2020’s domestic FP costing efforts to reverse-engineer these models for estimating FP funding requirements. Instead of refining expenditure estimates, it may be more useful for the FP community to instead focus on ensuring appropriate inclusion of FP within integrated health budgeting processes and financing schemes.

There is an urgent need to rethinking the approach to resource mobilization; in the post-2020 era, the old “playbook” needs an update that reflects the changing context.

Assumption 2: A coordinated partnership would enhance accountability for progress

Through a coordinated partnership, FP2020 also sought to enhance accountability for progress against the program and financial goals described above. The critical assumption was that enhanced data collection, transparent sharing of information, and celebration of success would be sufficient incentive for governments and providers to make more rapid progress than that realized to date.

Therefore, a key role of FP2020—and specifically the Secretariat—was to serve as a comprehensive and transparent collector, collator, and repository for disseminating data on financing and results. This vast collection of FP data is a direct result of investment in increased infrastructure and capacity globally. FP2020 collects an extensive set of core indicators, with some sources directly linked to FP2020 monitoring such as PMA2020. This effort is complemented by publicly available data on the state of FP commodity markets provided by the Reproductive Health Supplies Coalition and the Clinton Health Access Initiative. Together, these efforts have enhanced the capacity to design data instruments, expand data collection, and advance the basis for rigorous modeling. And, if used correctly and consistently, these efforts can contribute to continuous quality improvement through better decision making at the local, national, and global levels.

Key takeaway 2: Accountability requires a clear mandate; accountability and advocacy may not mix

FP2020 was designed as a donor-driven partnership; unlike a UN body, its legitimacy lies primarily with its ability to incentivize countries and entities with ample reason to make commitments—the implied promise of additional financial and technical resources. Ultimately, the FP2020 Secretariat, as the platform for the Core Partners, had limited levers to enforce real accountability. The Core Partners defined no clear entity to allocate or withhold resources in response to programmatic performance and therefore offered no clear ability or political appetite to “name and shame” underperforming organizations or governments. While transparent reporting has improved greatly since 2012, there is still little to no ability to hold individual governments or funders accountable for success or failure in achieving FP goals.[16] And, while celebrating successes is everyone’s role, calling out underperformers and/or enforcing consequences (both positive and negative) requires independent entity(ies) that hold requisite authorities.

Adding to the challenge, FP2020 often found itself torn between dual roles as an advocacy and accountability mechanism. Advocacy, particularly at the international level, tends to celebrate success—applauding new financial or programmatic commitments, highlighting progress, and more generally creating an attractive and positive atmosphere for the family planning community. Accountability, in contrast, is a fundamentally more somber function; it requires hard conversations and a direct reckoning with failure. In practice, FP2020 focused more on its advocacy function—potentially detracting from its ability to serve effectively as an accountability mechanism.

Looking past 2020, the FP community will need to address this accountability conundrum. What levers do donors and FP advocates have to enforce real accountability? How can the FP community better balance the competing needs for accountability and effective advocacy? And how can the Core Partners define a central coordinating body that has adequate levers to increase its legitimacy and authority, allowing it to play a more forceful role as “referee” among a diverse group of stakeholders?

Assumption 3: Harmonizing and aligning FP efforts would achieve greater efficiencies

FP2020’s initial design intentionally set a vertical structure intended to increase focused political commitment and financial support for FP. Year 2012 thinking rightly recognized that even if anticipated increases in financing were fully realized, funding flows alone would be insufficient to reach the aspirational program goal. Accordingly, the Partnership sought to realize efficiencies through harmonizing and aligning FP efforts across all parties.

The Core Partners designed the Secretariat as a platform for parties to come together to align efforts. An early concern of the broader FP community was how the Core Partners might link the goal of 120 million additional FP users to allocate—or reallocate—resources across countries. Somewhat compounding this tension, there was an assumption that each Core Partner had full control over how resources would be programmed in real time across countries. However, bilateral donor strategies are often underpinned by multiyear commitments and driven by influences beyond FP and health.

At the country level, FP2020 introduced costed implementation plans (CIPs) as a notionally country-led process to design and cost requirements to meet FP2020 commitments. The critical assumption was that CIPs would function as a singular tool with dual roles: to direct donor funding flows and leverage domestic resources. Some CIPs have helped set a broad direction for countries’ FP programs and served to secure significant buy-in from governments and civil society. But most experienced critical challenges and still exhibit important limitations that limit their utility as resource allocation roadmaps.[17]

When it became clear early on that CIPs and their anticipated program achievements were not linked to additional funding, the CIP process was severely undermined. And within the broader health landscape, CIPs were often perceived as occurring in isolation of the more integrated nature of domestic health financing approaches, including those countries directly working to realize UHC. While there is clearly a need to identify structural tools that allow for responsiveness to FP challenges, FP costed plans and investment cases must also be directly linked to—not isolated from—broader budget processes. Importantly, they should include model-based approaches to prioritize a blueprint (as opposed to a wish list) of where and how resources can be most impactful.

The dual challenge of steady or decreasing FP funding at the same time a country is aspiring toward UHC can be an opportunity to improve efficiencies while linking FP goals and planning with the larger health system. Another critical assumption with the CIP process was that existing health systems in many countries were strong enough for rapid expansion and only required “top up” to meet FP goals. Contextualizing FP within the broader UHC paradigm could help account for the health system’s strengths and weaknesses as part of a holistic costing process that covers the fully loaded costs at central and local levels.[18] UHC planning also incorporates valuable thinking beyond direct public sector services, including plans to engage social marketing, private pharmacies, and health care providers. This approach may also protect against the real possibility of FP losing support as health systems decentralize. Triangulating UHC plans, CIPs, and verified country level spending could help move closer toward estimates of the real need for FP spending and programming within health benefits packages. Nevertheless, if FP is to be included within UHC schemes, both political will and recognition of the central role of FP to overall health, empowerment, and prosperity will be required. Therefore, we recognize that ensuring FP inclusion in UHC planning is not as straightforward in practice. Ongoing efforts in several countries—Ghana is one example—will provide valuable lessons for the way forward.[19]

Key takeaway 3: time to align behind an integrated health financing approach while keeping the focus on accountability?

After seven years following a primarily vertical strategy, the evolving landscape suggests the time is ripe to test new tactics. A new and expanding financing platform, the GFF, now includes 36 countries—and all but one are FP2020 focus countries.[20] If adequately financed, the GFF offers an opportunity to firmly embed FP within each country’s larger strategy to support the health of women and girls. Yet the GFF is not currently resourced at a level that would allow it to fully deliver on this ambition, raising questions about its viability as an alternative channel for FP support. Further, the potential trade-offs between a focused, vertical approach and a more integrated approach require careful consideration. For example, if donors direct support for FP to the GFF, could FP dollars become “diluted”—potentially representing a net drop in total FP financing?[21]

Another critical question is whether the provision of high-quality, cost-effective FP services could be enhanced through a more integrated GFF (or UHC-based) approach. The onset of the GFF’s third year may offer the ability to better understand its potential impact on FP coordination and aligning donors around nationally defined and owned goals. Considering the current landscape, future efforts might invest in understanding the potential to realize synergies both within and beyond the health sector (the GFF’s investment case process is a potential avenue to explore). The post-2020 landscape offers the chance to explore integration of FP in UHC schemes, and together with the GFF in select countries—while attempting to better understand the resultant risks and benefits.

Recognizing that donors program resources consistent with their own goals and strategies, a possible post-2020 approach to achieving greater alignment at the global level could be for donors to coordinate longer term planning as countries transition away from external assistance.[22] Understanding the relative vulnerability of FP programs to abrupt country transitions can help identify countries in need of immediate-term strategies that bridge to longer-term approaches for funding and program sustainability. As countries increasingly move toward UHC, donor support for building capacity in areas such as developing insurance schemes, contracting, and procurement and supply chains will be critical to country self-sufficiency. In looking for greater efficiencies post-2020, the Core Partners might consider deepening ongoing coordination within countries; an approach that meets countries where they are along the continuum.

Conclusion

In charting a path forward, the FP community and its leadership can acknowledge the strengths and accomplishments, as well as the underlying assumptions, unanticipated outcomes, and structural challenges of FP2020’s initial model. This upcoming inflection moment points to the possible expansion in the number and types of stakeholders involved in strengthening and shaping the future of FP. Indeed, today’s FP2020 leadership has well communicated that the future will be built on an inclusive process and community ownership of next steps. We commend the approach to explicitly engage across the FP community to define post-2020 goals, including the public touch point planned at Women Deliver to disseminate the initial results of these efforts.

The next chapter of FP2020 will need to consider some hard questions around the paradigms that might be employed to advance country-level programming toward UHC at the same time donor FP and overall health financing flows are anticipated to stagnate or decrease. There will be no perfect strategy, however, there is value in reviewing FP2020’s underlying assumptions and their consequences. In designing approaches for the next decade, there is a continuing need to make explicit and ground truth underlying assumptions, foresee key challenges, balance inevitable trade-offs, and harness new opportunities. The post-2020 strategy will need to carefully consider the complexities of not just today’s context, but also of tomorrow’s anticipated landscape. In this, the new frontier, FP is central to advancing the multisectoral goals of individuals, communities, nations, and the planet.

[1] “Reproductive Choices to Life Chances: New and Existing Evidence on the Impact of Contraception on Women’s Economic Empowerment.” Center for Global Development, December 2017. /publication/reproductive-choices-life-chances-new-and-existing-evidence-impact-contraception-women

[2] This note expands upon CGD’s ongoing efforts in this space: The Aligning to 2020 Working Group, FP Leadership Retreat co-convened by CGD and the Kaiser Family Foundation, and our reflections from the 2018 International Conference on Family Planning, along with CGD’s ongoing efforts documenting the impacts of FP on women’s economic empowerment.

[4] See: https://partenariatouaga.org/en/west-africas-contraceptive-revolution-5-lessons-for-the-international-community/

[5] “Financing Global Health 2019: Countries and Programs in Transition.” Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation, 2019. http://www.healthdata.org/sites/default/files/files/policy_report/FGH/2019/FGH_2018_full-report.pdf

[6] “Protecting Life in Global Health Assistance.” US Department of State, May 2017. https://www.state.gov/r/pa/prs/ps/2017/05/270866.htm;

Rose, Sarah, Erin Collinson, and Jared Kalow. “Working Itself Out of a Job: USAID and Smart Strategic Transitions.” Center for Global Development, December 2017. /publication/working-itself-out-job-usaid-and-smart-strategic-transitions

[8] Edwards, Sophie. “View from the ground: International Conference on Family Planning 2018.” Devex, November 2018. https://www.devex.com/news/view-from-the-ground-international-conference-on-family-planning-2018-93840

[11] Global Burden of Disease Health Financing Collaborator Network. “Past, present, and future of global health financing: a review of development assistance, government, out-of-pocket, and other private spending on health for 195 countries, 1995–2050.” Lancet 393 (2019): 2233-60. https://www.thelancet.com/action/showPdf?pii=S0140-6736%2819%2930841-4;

Silverman, Rachel. “Projected Health Financing Transitions: Timeline and Magnitude.” Center for Global Development, July 2018. /sites/default/files/projected-health-financing-transitions-timeline-and-magnitude.pdf;

Silverman, Rachel and Amanda Glassman. “Aligning to 2020: How the FP2020 Core Partners Can Work Better, Together.” Center for Global Development, November 2016. /publication/aligning-2020

[13] Kavanaugh, Matthew and Lixue Chen. “Governance and Health Aid from the Global Fund: Effects Beyond Fighting Disease.” Annuals of Global Health 85 (2019): 1-9. https://agh.ubiquitypress.com/articles/10.5334/aogh.2505/

[14] “Expanding the fiscal space for health in Africa.” The Global Fund, June 2016. https://au.int/sites/default/files/pages/32895-file-expanding_the_fiscal_space_for_health_in_africa.pdf;

“Intertemporal Dynamics of Public Financing for Universal Health Coverage: Accounting for Fiscal Space Across Countries.” World Bank Group, December 2018. http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/639541545281356938/pdf/133115-19-12-2018-14-44-10-AccountingforFiscalSpaceinHealthFINAL.pdf;

Savedoff, William. “New High-Level Report Calls for Higher Taxes on Tobacco, Alcohol, and Sugary Beverages to Prevent Millions of Deaths.” Center for Global Development, April 2019. /blog/new-high-level-report-calls-higher-taxes-tobacco-alcohol-sugary-beverages-prevent-millions

[16] Silverman, Rachel and Roxanne Oroxom. “Dear Donors: Three Recommendations to Accelerate Progress Toward the Global Family Planning Goals.” Center for Global Development, November 2016. /blog/dear-donors-three-recommendations-accelerate-progress-toward-global-family-planning-goals;

[17] Silverman, Rachel and Amanda Glassman. “Aligning to 2020: How the FP2020 Core Partners Can Work Better, Together.” Center for Global Development, November 2016. /publication/aligning-2020;

Silverman, Rachel and Roxanne Oroxom. “Dear Donors: Three Recommendations to Accelerate Progress Toward the Global Family Planning Goals.” Center for Global Development, November 2016. /blog/dear-donors-three-recommendations-accelerate-progress-toward-global-family-planning-goals

[18] “Health Financing and Family Planning in the Context of Universal Health Care: Connecting the Discourse in Kenya.” Population Council, March 2019. https://www.popcouncil.org/uploads/pdfs/2019RH_HealthFinancingKenyaBrief.pdf

[19] See: https://blogs.worldbank.org/africacan/taking-stock-financing-family-planning-services-to-reach-ghanas-2020-goals

[20] See: https://www.globalfinancingfacility.org/nine-countries-join-global-financing-facility-now-reaching-36-countries-greatest-health-and

[21] Silverman, Rachel and Amanda Glassman. “Aligning to 2020: How the FP2020 Core Partners Can Work Better, Together.” Center for Global Development, November 2016. /publication/aligning-2020

[22] Apter, Felice, Amanda Glassman, Janeen Madan Keller, Jen Kates, Kellie Moss, and Adam Wexler. “The USG International Family Planning Landscape: Defining Approaches to Address Uncertainties in Funding and Programming.” Center for Global Development, May 2018: /publication/usg-international-family-planning-landscape-defining-approaches-to-address-uncertainties

Rights & Permissions

You may use and disseminate CGD’s publications under these conditions.