Recommended

POLICY PAPERS

Publicly funded international climate finance—while still short of Paris Agreement targets—has grown quickly in the last decade, and looks set to continue to do so. Last month, at COP27, we saw the first round of negotiations on a new climate finance goal from 2025 which will increase finance from a floor of $100 billion a year; and a landmark agreement on “loss and damage” funding, for which providers have already pledged over $300 million.

But in a new paper, published alongside the conclusion of the high-level summit of the Global Partnership for Effective Development Cooperation (GPEDC) in Geneva, we find that the fast rise of climate finance has come with a number of troubling signs for how well that money is spent. This analysis substantiates a number of issues raised by recipients who have been calling out for more predictable, accessible, and affordable climate finance.

In this blog, we briefly summarise six worrying trends in how climate finance is being spent, and recommend the GPEDC set up a working group on climate finance, alongside three other recommendations for policy-makers at bilateral and multilateral development agencies; as well as those working on the new climate finance goal with the UNFCCC.

Climate and development need to be tackled together but the trends we observe suggest that climate-related finance needs some special attention...

The rise and rise of climate finance

Climate finance totals reached over $83 billion in 2020, with the “lion’s share” coming directly from public budgets. Climate-relevant projects now account for a third of bilateral aid spending (official development assistance or ODA), and almost a quarter of outflows from ODA-eligible multilaterals. These shares can be expected to grow even further over the next decade—indeed, tackling global challenges like climate change and its effects in lower- and middle-income countries is set to become the leading motivation for providing ODA among development agencies in the next ten years.

Development agencies are largely responsible for managing this growth and, where concessional climate finance is not additional to existing development budgets, managing any trade-offs. At a discussion of policymakers we hosted with the Konrad Adenauer Stiftung last week, we heard broad recognition that climate and development programming could not be separated; but that trade-offs exist and agencies should tailor instruments and policies to ensure the efficient use of scarce resources, for example by targeting grants towards adaptation in the poorest partners, providing loans and encouraging fossil fuel subsidy reform for higher emitters, and using the right tools to incentivise the private sector. Questions also remain on how climate projects should be allocated and evaluated to account for both global and local co-benefits.

Evidence on climate finance quality

Years of trial and error have enabled development practitioners to forge a consensus around four key principles for guiding effective development programmes: recipient country ownership, transparency and mutual accountability, inclusive development partnerships, and a focus on results. Yet more than a decade on from the latest effectiveness agreement and the creation of the GPEDC to monitor progress, there is little evidence as to how the effectiveness principles have been implemented or operationalised by climate finance providers. We set out to fill this gap by exploring the available evidence in areas related to each principle.

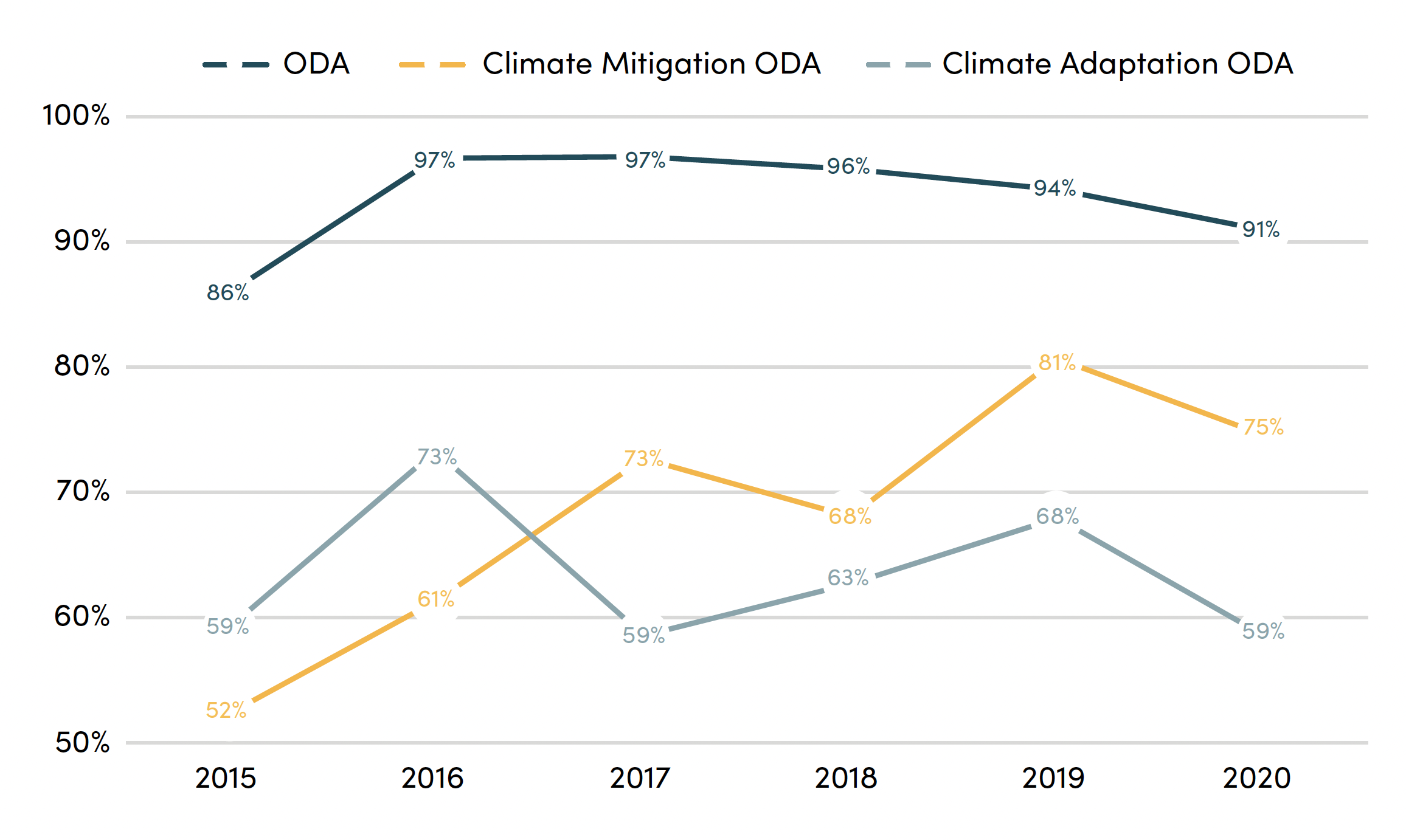

We find six challenging trends for climate-related development finance relative to other official development flows. Firstly, committed climate finance is not being delivered to recipients at the same rate or speed as other types of development finance (Figure 1). This both limits trust and inhibits recipients’ ability to plan. Second, we note that despite frequent calls from recipients for more grant-based funding, over two-thirds of climate finance is provided as loans—a higher share than across total official flows to ODA-eligible countries (52 percent). Third, we find that an increasing proportion of climate mitigation finance is being allocated “beyond the country level” (i.e., not to a specific country), with this share reaching 29 percent in 2020. This allocation pattern—while arguably better suited towards the provision of global public goods—makes it harder to integrate projects with existing national-level strategies, impossible to achieve “local ownership”, and raises questions about whether the main benefits of development finance are for developing countries.

Figure 1: Disbursement ratios in 2015-2020, for all ODA and ODA with climate objectives

Source: OECD CRS. As the analysis is based on Rio Markers, it excludes most MDBs.

Note: When reporting onannual commitments, the CRS uses “moving averages in statistical presentations to smooth the resulting fluctuations”, meaning that commitments represent an approximation of the planned annual spend, rather than gross total of multi-year project.This means that regardless of the faster-than-average growth rate in climate-related ODA, annual disbursement ratios should still be reflective of project delays or cancellations.

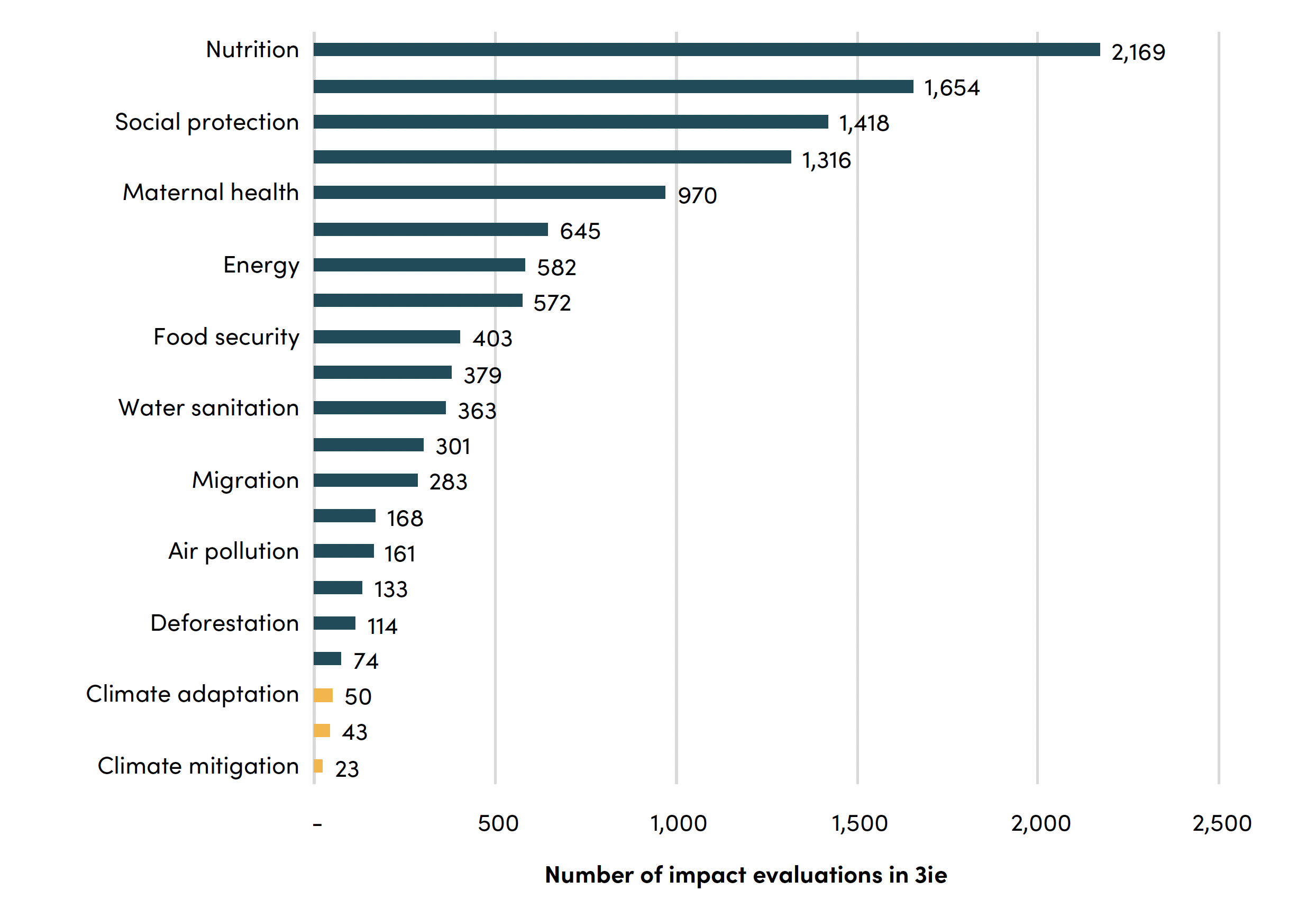

Fourth, we find that since 2015, the number of active climate finance providers has sharply increased, even as the average size of climate projects has fallen by around a third. While proliferation and fragmentation have been widely noted across the broader development financing landscape, the rate of change is greater in climate finance, leading to additional transaction costs for recipients. Fifth, we observe that only a small share of climate finance is delivered directly to governments as budget support (7 percent compared with 15 percent for total ODA in 2020). Instead, funding is mostly committed for specific projects, which creates a risk that investments will fail to create synergies with other ongoing activities, and are not integrated with wider government processes. The sixth and final trend we explore is the lack of systematic efforts to evaluate the impacts of climate interventions as compared with other areas where development finance is channelled (Figure 2). If providers had clear evidence of the results of climate finance, they would be more confident in allocating funding, reducing burdens and improving access for recipients, but the current situation does not allow policymakers to form insights on pre-conditions for success.

Figure 2: Number of impact evaluations recorded by keyword

Source: Authors’ synthesis from 3ie

Who needs to act?

The need to design development programmes that are climate-resilient and Paris-aligned is clear for policymakers everywhere, but we make the argument for four specific actions. First, bilateral and multilateral development agencies should consider their own performance on the trends outlined in this paper and other measures of effectiveness, and set goals to improve the predictability, affordability, and share of their climate finance channelled via recipient-owned institutions. Second, providers should strengthen their efforts on evaluating the impact of climate interventions, and—given the common nature of climate challenges—establish coordination mechanisms to enable greater comparability of “what works” across a wide variety of climate-relevant contexts and sectors.Third, the Global Partnership for Effective Development Cooperation, GPEDC, and its new chairs, should set up a dedicated climate finance effectiveness working group to take forward regular assessments of climate finance and share learnings between development partners—including through dedicated engagement with specialised multilateral climate funds—and climate-vulnerable partner countries. Finally, policymakers working at and with the UNFCCC should consider the quality of climate finance during the design of the new collective quantified climate finance goal to ensure that its structure promotes accountability and increases recipients’ ability to trust in the climate finance architecture.

Conclusion

Climate finance is too important to be ineffective. While climate finance is still a relatively new type of development flow, decades of experience in other sectors mean that official development finance providers have likely faced similar challenges before, and made some progress. It is important that these past lessons are taken on and used to improve the quality of climate finance.

Disclaimer

CGD blog posts reflect the views of the authors, drawing on prior research and experience in their areas of expertise. CGD is a nonpartisan, independent organization and does not take institutional positions.