It’s too early to know how large the economic impact of Ebola will be on West Africa and the world. Past experience, including the 2002-03 Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS) epidemic, suggest it could be very large indeed, especially in the African countries that have been hardest hit. Fortunately, actions that the US and other donor countries take now could help not only to control the epidemic but also to minimize the economic fallout.

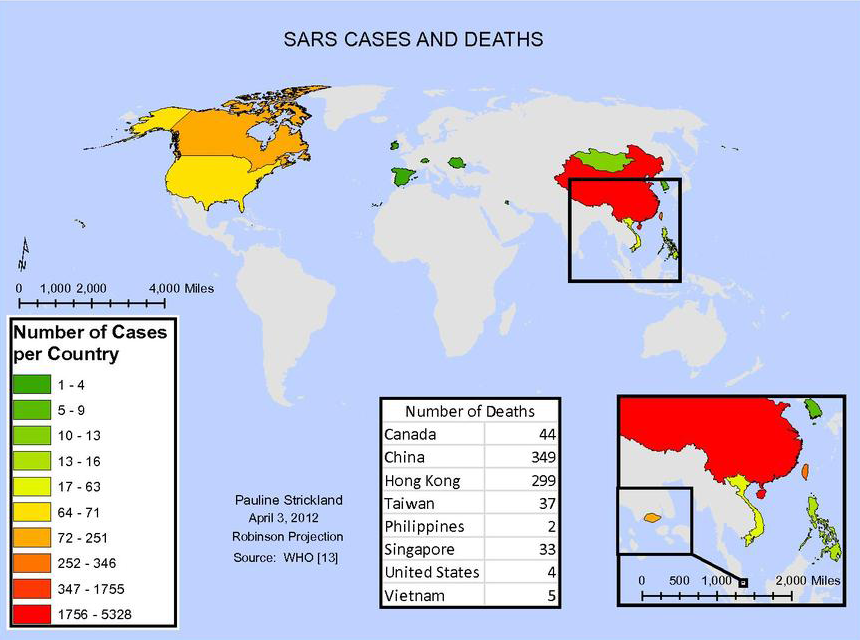

Ebola has now been reported in eight African countries, recalling the rapid spread of SARS throughout Asia. Just as SARS spread to North America and Europe we should expected isolated cases of Ebola to appear outside of West Africa. (See Figures 1a and 1b.)

Figure 1b. Current Ebola Outbreak. (Source: National Geographic). Click image for larger version.

Figure 1b. Current Ebola Outbreak. (Source: National Geographic). Click image for larger version.

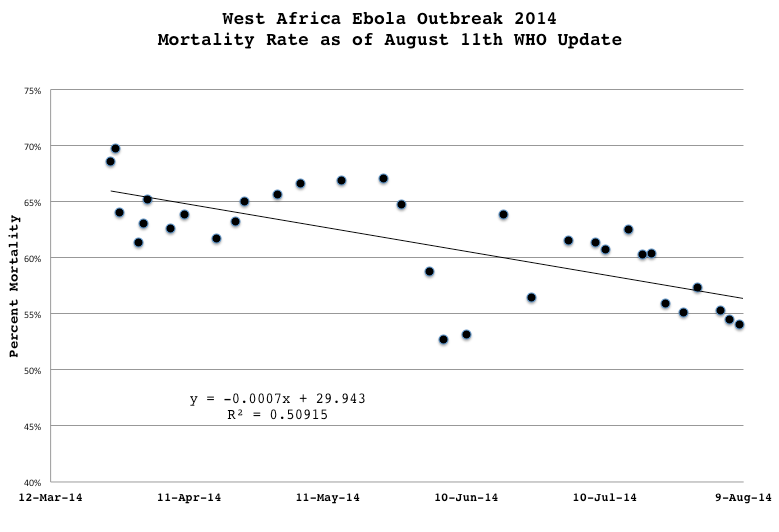

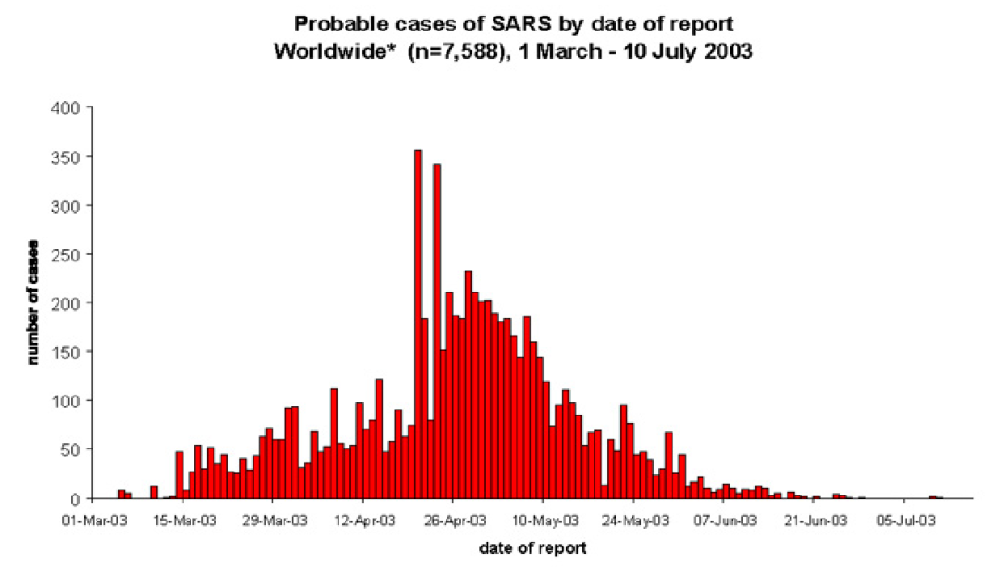

The number of cases of SARS increased every week for two months before beginning to decline. The number of cases of Ebola continues to increase each week, but we can hope that with the dramatic increase in national and international attention to the disease, the number of weekly cases will soon peak and begin to decline.

Figure 2b. Probable worldwide cases of Ebola, April-August, 2014. (Source: Ebola Update by Greg Laden, Science Blogs August 12, 2014.) Click image for larger version.

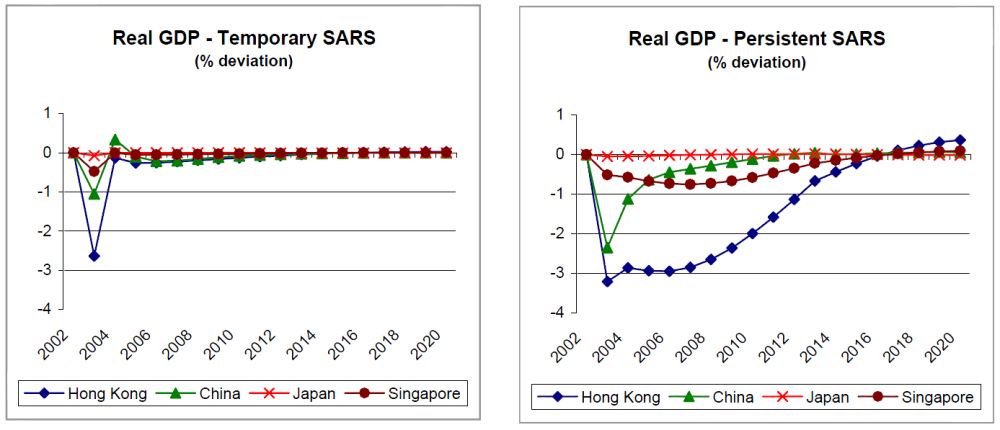

There have been several studies of the economic impact of the 2002-3 SARS epidemic, but the one I find most useful is a study by Lee and McKibbin entitled Estimating the Global Economic Costs of SARS (also available as a Brooking working paper here). The authors use a dynamic computable general equilibrium model to project the eventual cost of the SARS epidemic for individual countries and the world as a whole.; Figure 3 reproduces their graphical results for two alternative assumptions regarding the expectations of economic decision-makers (whom Lee and McKibbin call the “economic agents”).

If the millions of individual decision-makers believe that the SARS epidemic is a rare anomaly, the authors’ model projects the total worldwide cost of SARS in a single year, 2003, to be $40 billion. Since there were only about 8,500 cases of SARS and about 800 deaths, that works out to $4.7 million per case or about $50 million per SARS death. This amount is of course far more than the lost economic product of the 8,500 sick people. It results from the reductions in trade, investment, tourism, business travel and service sector activity caused by either personal fear of SARS or fear that others will fear SARS. The left panel of Figure 3 shows the resumption of normal economic activity if that fear quickly dissipates by 2004.

But this is the optimistic view. What if fears persist? What if peoples’ panic about SARS (and Ebola?) continue to inhibit trade, investment, travel and service sector activity for several future years? First, Lee and McKibbin predict that even the 2003 impact would be 35% greater ($54 billion instead of $40 billion), because a third of economic decision-makers foresee the persistent fear and reduce their economic engagement in the affected countries. Then, as can be seen in the right panel of Figure 3, Lee and McKibbin predict that Hong Kong and Singapore would have almost equally large impacts over the subsequent five years.

Related

- Aversion Behavior Exacerbates the Economic Impact of Ebola (Blog)

- Unpacking WHO’s Shocking Ebola Maps–Mead Over (Wonkcast)

- CDC vs Médecins Sans Frontières on Ebola: Is the Perfect the Enemy of the Good? (Blog)

- Finding a Cure for Ebola (Blog)

- Understanding the World Bank’s Estimate of the Economic Damage of Ebola to West Africa (Blog)

- Obama’s Ebola Response and a Plea from Liberia (Blog)

- "We Are Running Out of Time" – A Letter from the Front Lines of Ebola (Blog)

- Contagion: Help Congress Protect the CDC’s Outbreak Investigation Budget (Blog)

If the Ebola epidemic can be controlled as rapidly as the SARS epidemic, and the economies of Liberia, Guinea and Sierra Leone are like that of Hong Kong, we might predict that fear of Ebola will cause their 2014-15 economies to grow 3% more slowly than they otherwise would. On average this would be about a 40% reduction in growth for the next 12 months.

But the three African economies are different from Hong Kong in important ways: they are far more fragile, with weaker institutions and epidemic control systems; but they are also far less dependent on trade. These factors offset one another, making it hard to know whether these economies will suffer more or less economic damage than Hong Kong did in 2003.

The US should act jointly with other countries to facilitate the return of full air service to the cities of Monrovia, Conakry and Freetown. This is not easy, but it is essential both to facilitate the control of the Ebola outbreaks and to assure that investment and trade can continue with as little interruption as possible. Specific policies that will enable the airlines to continue serving include:

- Require any airline that continues to serve Conakry, Monrovia and Freetown to offer hazard pay to crews who work those routes.

- Subsidize the hazard pay for airline crews and all additional expenses airlines incur to travel these routes.

- Establish comfortable, hotel-like isolation and quarantine facilities not only at the airports of Conakry, Monrovia and Freetown, but also at major international airports that serve those countries.

- Subsidize travel to and, especially, back from the affected countries of international health volunteers, including subsidizing their isolation and quarantine in the airport facilities when necessary and fully underwriting their treatment should they contract Ebola.

- Dismantle the above arrangements gradually over 2015, as the imminent danger from Ebola subsides.

These measures will be expensive, perhaps equaling the $495 million cost WHO has estimated in their recently published “roadmap” for epidemic control. Nonetheless they would be a prudent investment in minimizing the economic impact of the disease on some of the world’s poorest countries, several of which are fragile democracies slowly recovering from prolonged civil wars.

With strong support to the people of the affected West African countries, the international fear of Ebola and the consequent aversion behavior towards these countries can be limited and the duration and magnitude of the economic consequences reduced.

Disclaimer

CGD blog posts reflect the views of the authors, drawing on prior research and experience in their areas of expertise. CGD is a nonpartisan, independent organization and does not take institutional positions.