Recommended

Blog Post

Read about the survey results here.

COVID-19 is likely to affect the education outcomes of girls and boys in adverse and differential ways, as researchers and policymakers, including our CGD colleagues, have documented. What has been less studied are the challenges and perceptions of the organizations delivering vital educational services to girls and boys in low-income countries: the nongovernmental organizations, school operators, and other service providers whose operations have been disrupted indefinitely by school closures and lockdowns.

To better understand their challenges, we are launching the Out of School Girls Survey. We aim to illuminate some of the short- and long-term gender-related concerns of those with firsthand knowledge of how the crisis is affecting the girls and boys they serve. Please share the survey widely and encourage your contacts working in frontline organizations to complete it.

Here’s how school closures may differentially affect girls, and a little more on why we’re launching the Out of School Girls Survey.

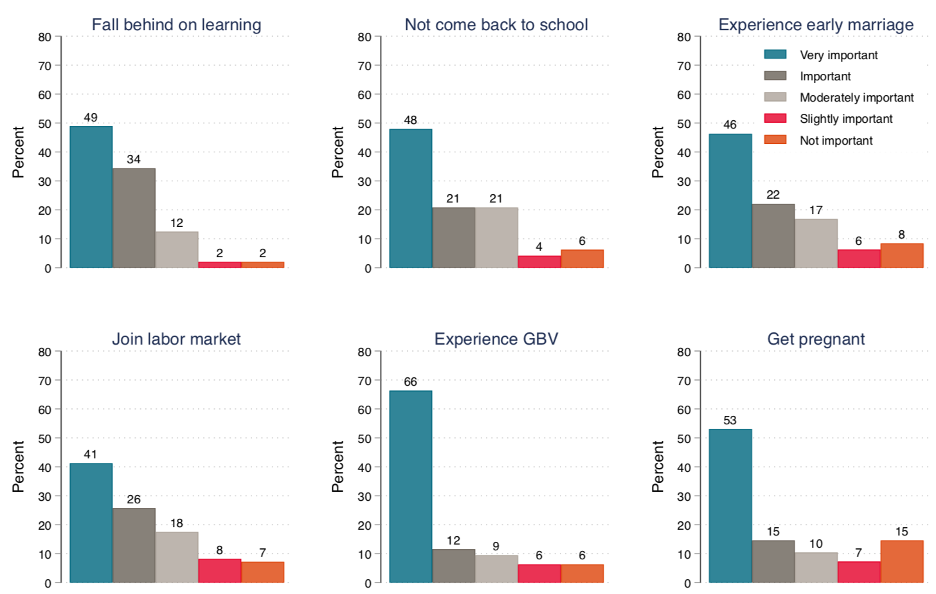

We already know that school closures will intensify risks for girls

Keeping girls in school has transformative effects on their lives, as well as the lives of the next generation. Every additional year in school increases a girl’s future income generation by 10 to 20 percent. And keeping girls in school also increases human capital for future generations: more educated mothers are better able to invest in the health and education of their children. Girls who stay in school are less likely to have unsafe sex, contract HIV or other sexually transmitted infections, or marry and have children when they are still children themselves.

In response to COVID-19, schools have closed in 188 countries across the world. In many countries, there is no definitive date for when they will reopen. UNESCO estimates 91 percent of the world’s children are out of school, including 743 million girls. One hundred million of those girls live in the world’s poorest countries. School closures have widespread implications for both girls and boys. We’ve already highlighted consequences for school-feeding programs that children rely on for nutrition, for testing to assess students’ skills, and for overall learning.

Even before COVID-19 closed schools around the world, tens of millions of girls already faced pressure to drop out of school to care for siblings, do unpaid domestic work, contribute financially to their households, or marry and have children. Out-of-school girls are also at an increased risk of sexual exploitation—adolescent girls living in poverty encounter pressures to engage in intercourse with sexual partners who can provide financial or in-kind support. Approximately 13 million adolescent girls in low- and middle-income countries become pregnant before the age of 20 and face additional health risks: higher rates of eclampsia, puerperal endometritis, and systemic infections.

Now couple adolescent girls’ existing vulnerabilities with those brought on by the crisis. During an epidemic or pandemic, households face increased economic strains due to lost income brought on by health shocks, lockdowns, and social distancing measures to contain the outbreak. Recent data from Bangladesh shows that COVID-19 lockdowns led to a more than fourfold fall in incomes in one village. In response to economic shocks, girls may shift their activities toward purely income-generating activities to support their households and forego educational activities, as seen in Sierra Leone during the Ebola outbreak. Evidence from sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia suggests that, when faced with limited resources, households may prioritize sending boys to school rather than girls—raising concerns about whether girls will come back to schools at all.

Household income shocks may also increase the risk of girls being married early. Evidence from sub-Saharan Africa suggests that local income shocks may increase child marriage for girls because marriage payments may be a source of consumption smoothing . (The same study did find the opposite pattern in India.) Income shocks may also increase the likelihood of girls experiencing coerced or transactional sex. During the Ebola outbreak, adolescent pregnancies in some parts of Sierra Leone increased by 65 percent. These economic and social pressures may further reduce the likelihood of girls returning to school once they reopen. Without intervention to ensure out-of-school girls spent time in productive activities with other girls their age, Bandiera et al. find that during the Ebola crisis in Sierra Leone out-of-wedlock pregnancies rose, and girls experienced a 16 percentage point decrease in school enrollment once schools reopened.

How can policymakers respond, with the knowledge we have now?

While we gather new data specific to the COVID-19 pandemic, existing evidence from past pandemics and other crises provides some lessons for how we can insulate girls from some of these risks:

-

Prioritize economic support to vulnerable girls and their households. Governments, with donor support, could consider providing cash transfers as a means of ensuring a social safety net for vulnerable populations. Targeting transfers towards low-income households would help adolescent girls who are more likely to face pressures to marry or engage in transactional sex due to economic shocks. Governments could also explore making longer-term transfers conditional on girls’ re-entry into school. Evidence suggests that unconditional and conditional cash transfers can work as complements to relieve economic strain and increase girls’ human capital. School operators like The Citizens Foundation in Pakistan are already stepping up to provide cash transfers to families of vulnerable students in response to school closures.

-

Model (and adapt) interventions proven to benefit girls. The Empowerment and Livelihood for Adolescents intervention, delivered by BRAC in Sierra Leone during the Ebola outbreak, is one model to emulate. To respond to social distancing requirements, adaptations will likely be necessary, including by engaging girls with mobile technology and edutainment platforms where possible. In preparing for future pandemics and to mitigate the consequences of COVID-19, policymakers must prioritize closing the gender digital divide.

-

Sustain provision of sexual and reproductive health services. Fertility rates rise during pandemics. Marie Stopes International predicts that the loss of sexual and reproductive health services could result in as many as 3 million additional unintended pregnancies, 2.7 million unsafe abortions, and 11,000 pregnancy-related deaths. While health services that are overburdened with COVID-19 have stopped nonessential procedures, it is important to try to continue providing demand-driven contraception and related support services to mitigate unplanned and unsafe pregnancies among adolescent girls.

-

Plan to institute incentives to help girls return to school. In the aftermath of past pandemics, governments have acted to ease economic vulnerabilities and incentivize children’s re-entry into school. In the wake of Ebola, the government of Sierra Leone announced measures to ease financial burdens on families, including waiving standard examination fees and subsidizing secondary school matriculation fees for two years. Following COVID-19 school closures, governments should prioritize similar measures that incentivize both girls’ and boys’ re-entry into school.

But we need more data specific to COVID-19 data to craft the best responses. A new CGD survey can help.

These are important steps policymakers can take now. But COVID-19 will create specific, unique risks for girls, and the most effective responses will require an understanding of that.

The first step is to learn from those at the frontlines about the specific risks posed to girls by school closures. More context-specific data can help policymakers, donors, and practitioners make more informed decisions. That’s why we’re launching the new Out of School Girls Survey. Once again, if you work with an organization on the frontline of education service delivery—school operators; other education service providers; and organizations delivering children's rights, childcare, or gender equality programs in education systems—we encourage you to take the survey and share it widely.

Thanks to Lee Crawfurd for helpful comments.

Disclaimer

CGD blog posts reflect the views of the authors, drawing on prior research and experience in their areas of expertise. CGD is a nonpartisan, independent organization and does not take institutional positions.

Image credit for social media/web: Photo by Sarah Farhat / World Bank