Disclaimer

CGD blog posts reflect the views of the authors, drawing on prior research and experience in their areas of expertise. CGD is a nonpartisan, independent organization and does not take institutional positions.

This blog is one in a series by experts across the Center for Global Development ahead of the 2022 US-Africa Leaders Summit. These posts aim to re-examine US-Africa policy and put forward recommendations to deliver on a more resilient, deeper, and mutually beneficial partnership between the United States and the nations of Africa.

President Hebert Hoover, who is often credited as one of the earliest champions of America’s leadership in providing assistance to feed school children globally, once said “civilization marches forward upon the feet of healthy children.'' In a way, the long history of the United States in expanding school meals around the world can trace its origin to the large-scale effort Hebert Hoover orchestrated to deliver food relief to children and families in Europe in the aftermath of the two world wars. More recently, the mantle of delivering school meals to children in need, particularly in Sub-Saharan Africa, has been carried by the McGovern-Dole Food for Education Program, a global program donating US food, run out of the Department of Agriculture.

As the US-Africa Leaders Summit kicks off, and with food security being a top policy issue, delegates would be well placed to advance this long-term cooperation between the US and Africa on school meals. Hunger at school is a fast-growing barrier to learning in rich and poor countries alike. With food prices escalating globally, there is an urgent need for renewed partnerships between the US and African governments to sustain school meal programs around the continent. African Leaders at the Summit should commit to feeding children in school. And the US should commit to a plan to help them finance it.

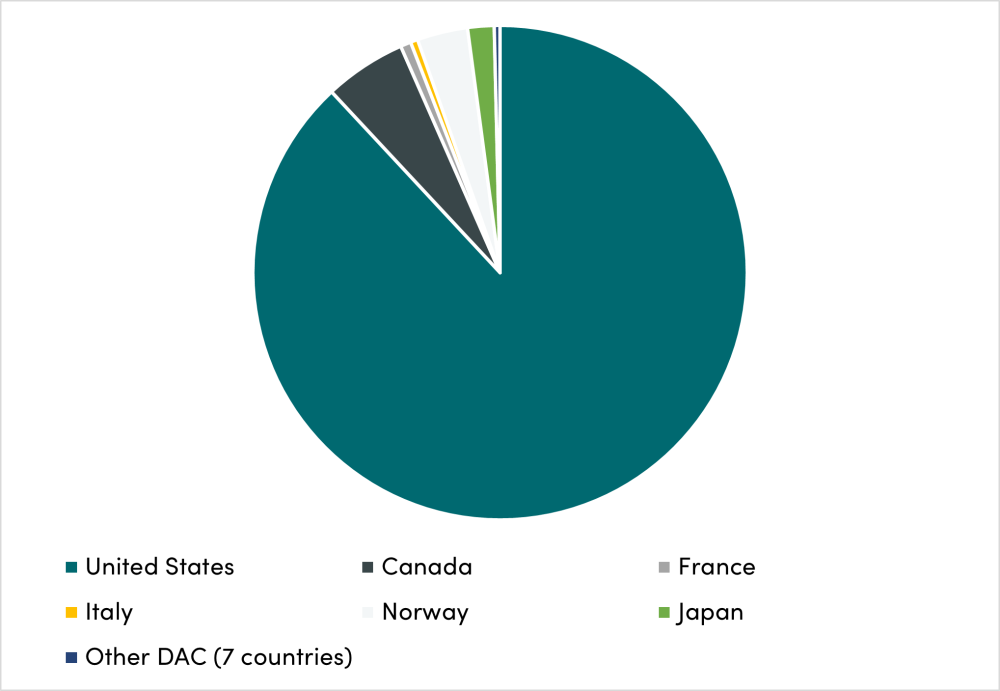

Nearly 90 percent of all bilateral aid financing by OECD-DAC donors for school meals in Africa comes from the US Government (figure 1). This is something which the US should be proud of. School meals are one of the best educational investments money can buy. They increase attendance, improve learning and reduce drop out, especially for the most disadvantaged children.

The US is notable among donor countries for clearly aligning its international education aid strategy with its food assistance program. For instance, the current US government strategy on international basic education identifies the provision of daily school meals as one of the activities US government programs need to encourage “to increase the percentage of students who attain a minimum proficiency in reading and math”. The fact that the policy recognizes school meals, in addition to mainstream pedagogical and capacity building interventions, as a strategy to improving learning outcomes is an encouraging sign of coherence.

Figure 1. Share of financing of school meals in Africa by bilateral donors (2018-2020)

Source: OECD Creditor Reporting System

The McGovern-Dole program was established under George W Bush in 2002. Two decades later, it still receives bipartisan support as a flagship international human development program. The design of the program—run by the Department of Agriculture—as a means to mop up excess supply of US agricultural products—might have contributed to the continued support through alignment with politically salient domestic interests. The program survived a bold attempt by the Trump administration to eliminate it in 2017 with only marginal reductions in total funding partly due to the strong support it garnered in congress.

This design—buying food from American producers to send to Africa—is not without its critics. Some believe that shipping US grain to Africa undermines local markets and drives prices down for producers. But, many of the countries that benefit from the program are net importers of food—in fact 51 percent of countries in sub-Saharan Africa procure internationally for their school feeding programs (whether domestic or aid funded). And the current food crisis demonstrates how reliant many of those countries are on food from Ukraine and Russia.

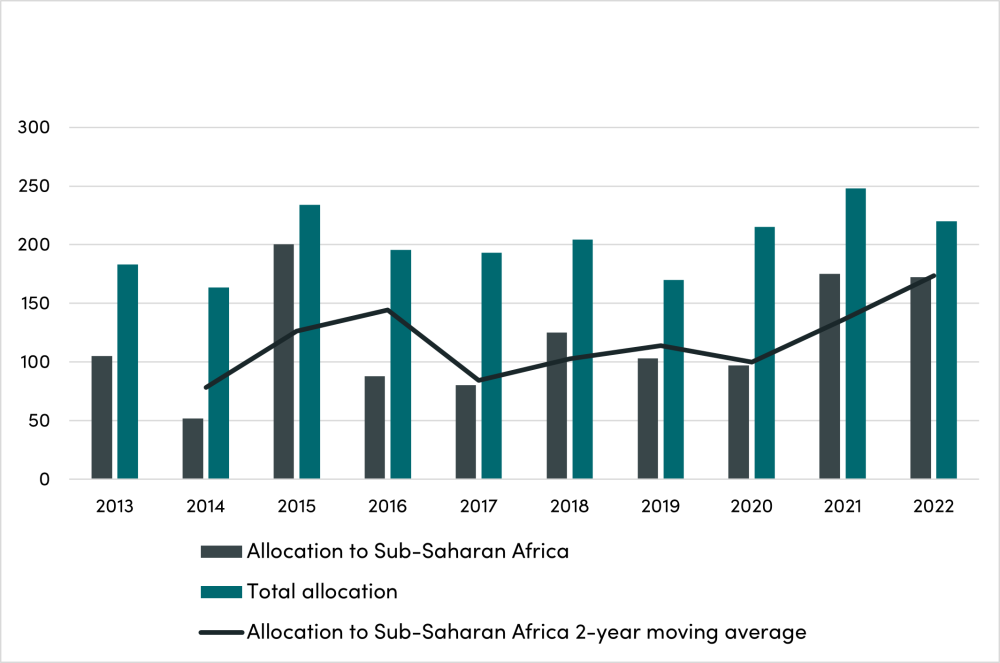

Figure 2. McGovern-Dole Food for Education funding ($million)

Source: US Department of Agriculture

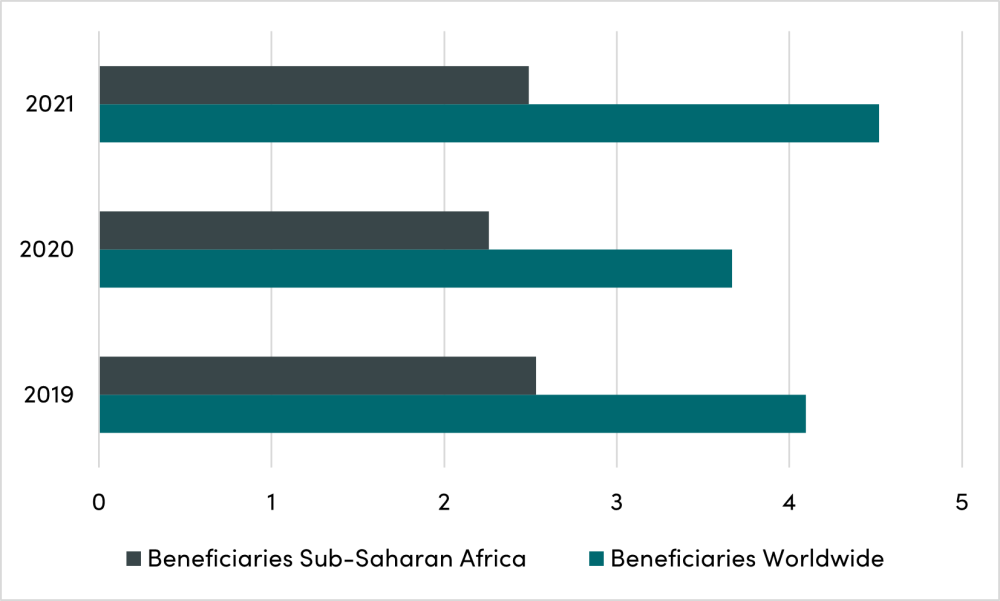

The program has allocated an average of $202 million per year to school feeding over the past decade (figure 2)—more than 10 percent of all US aid to education— spanning both democratic and republican administrations. This amount is usually parceled into eight program grants that are awarded competitively to partner organizations operating in low and lower-middle income countries. Allocations to Sub-Saharan African countries have on average accounted for 59 percent of the grants each year. And it’s fed a lot of children. Over the last 3 years, including the COVID 19 pandemic, more than 7 million children across the region have received school meals through the McGovern-Dole program (figure 3).

Figure 3. Beneficiaries of the McGovern-Dole Program in Sub-Saharan Africa (in millions)

Source: US Department of Agriculture

The McGovern-Dole program has set a model, along with other programs run by international organizations such as the World Food Programme, for national governments in developing countries to take on school feeding from their national budgets. As of 2021, 16 out of 37 Sub-Saharan African governments cover more than half of their school feeding expenditures out of their national budgets. But global food price shocks have made domestically-funded school meals programs vulnerable and many countries are struggling to sustain their programs against the headwinds of global food price increases and mounting national debt.

The US-Africa Leaders Summit is the right venue for the US to reiterate and increase its commitment to school meals in Africa. As domestic programs hang in the balance, the US can offer support to African governments by donating US food alongside financial and technical assistance to support school feeding programs in countries where fiscal constraints leave them vulnerable. And beyond this, the US-Africa summit has the opportunity to influence other donors and governments to finance school meals. The US is a founding member of the School Meals Coalition, alongside 25 countries in sub-Saharan Africa and can use this platform to influence other donor members—Norway, Finland, France, Germany, Japan—to up their funding of school meals as well as encourage other allies to join the Coalition.

Food security and education are two of the eight priority policy areas at the Summit. And US policy has already taken the laudable step of recognizing school meals as one of the tools to tackle the current learning crisis. Each additional dollar investment in school meals has the potential to go a long way from improving learning outcomes to promoting school enrollment of girls and disadvantaged children. A commitment at the Summit by US and African leaders to feed even more children in school would be a legacy to be proud of.

Thanks to Erin Collinson for her comments on this blog

CGD blog posts reflect the views of the authors, drawing on prior research and experience in their areas of expertise. CGD is a nonpartisan, independent organization and does not take institutional positions.