Of the 80 million teachers worldwide, more than half are female. This International Women’s Day we offer six facts about the share, location, role, and prospects of the 45 million female teachers globally.

We show that while most developed countries have a higher share of female teachers, women in sub-Saharan Africa still compose a minority in the profession. Female teachers tend to be concentrated in the earlier years of school, and, while they’re are just as qualified as their male counterparts, they do not advance proportionally to leadership positions in schools.

Female teachers are important for education systems and for gender equality. Evidence suggests that female teachers may increase girls’ test scores and their likelihood of staying in school, heighten their aspirations, and lower their likelihood of being subject to violence. And the teacher labour market is important for women: in some countries, teaching is one of the few high skilled professions that is accessible to women.

1. There are large variations in the percentage of female teachers among regions, with more in rich countries

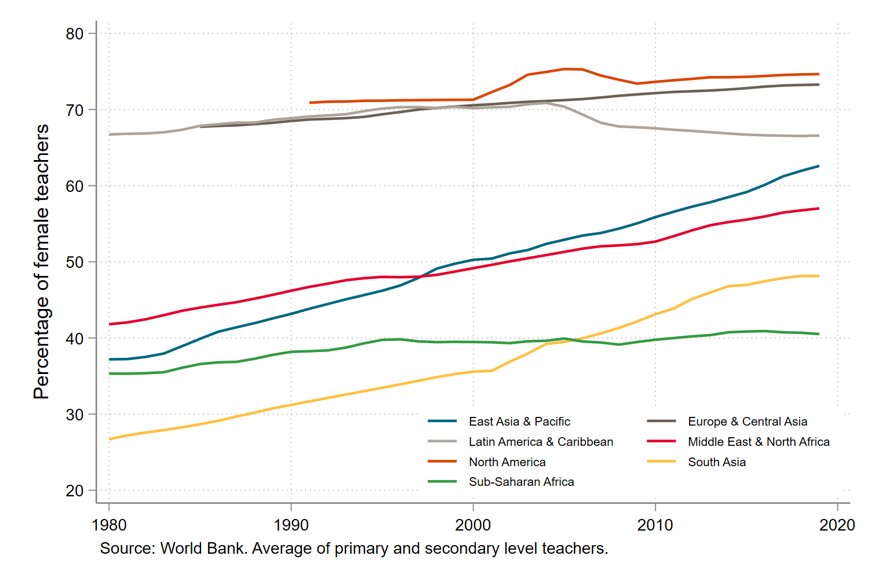

Although, globally, close to 60 percent of teachers are female, there are considerable variations among regions. In Europe, Latin America, and North America women have made up roughly 70 percent of all teachers since the 1980s, and the teaching profession has been women-dominated for much longer in some areas. At the primary grade level, the United Kingdom reached 70 percent of female teachers by 1901 and Argentina 85 percent by 1930 (Kelleher et al., 2011). Most regions of the world have a large and increasing share of female teachers, except sub-Saharan Africa, which has a low share of female teachers with little change over time.

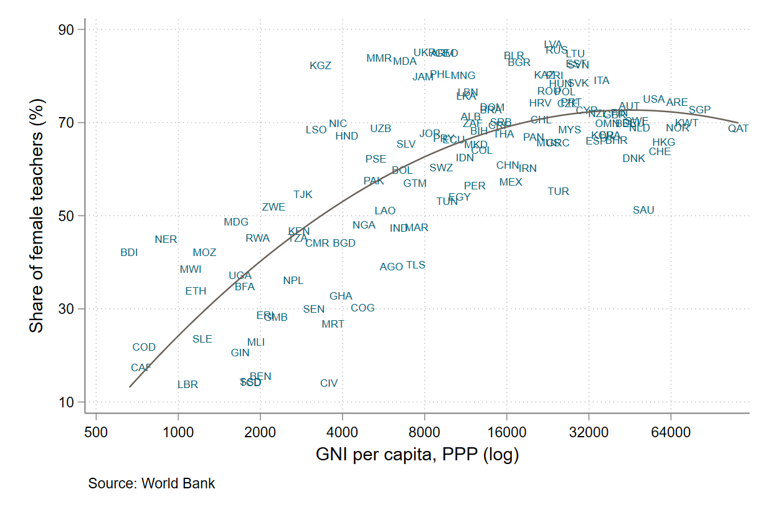

One explanation behind these large differences between regions is the strong association between a country’s level of development and the share of female teachers in a country. In the poorest countries in the world, female teachers are rare, making up less than 15 percent of all teachers in Côte d’Ivoire, Liberia, and Chad. But as countries get richer, the share of female teachers increases rapidly and there are no countries with more male than female teachers above $8,000 gross national income (GNI) per capita (adjusted for purchasing power).

2. The share of female teachers is higher in urban areas

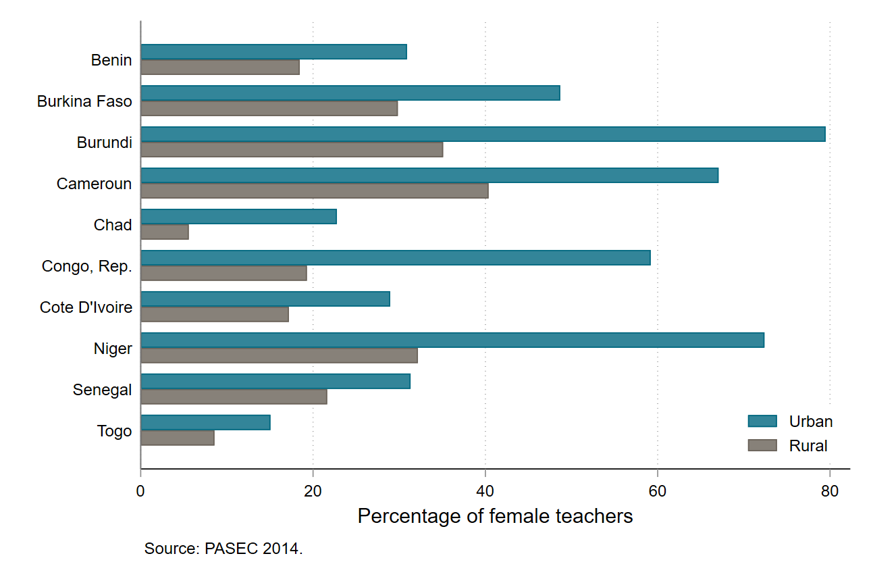

Female teachers tend to be located primarily in urban areas. For instance, in India women make up 65 percent of teachers in urban areas versus 37 percent in rural areas (Kelleher et al., 2011), with similar results found in Lesotho and Sri Lanka. There is no global dataset on the location of female teachers, but we looked into PASEC data from 2014, which includes information for primary schools in 10 francophone African countries. All 10 show the same pattern: urban areas show a much larger share of female teachers than rural, with an average of twice the percentage of female teachers in urban areas (46 percent) than in rural areas (23 percent).

Figure 3. Percentage of female teachers in urban and rural areas of 10 African francophone countries

Safety, more conservative values, or the difficulty to take a job far away from their family might explain why women are less likely to teach in rural areas. But this means girls in rural areas are less likely to have a female teacher, when they could benefit the most from being in contact with a qualified working woman.

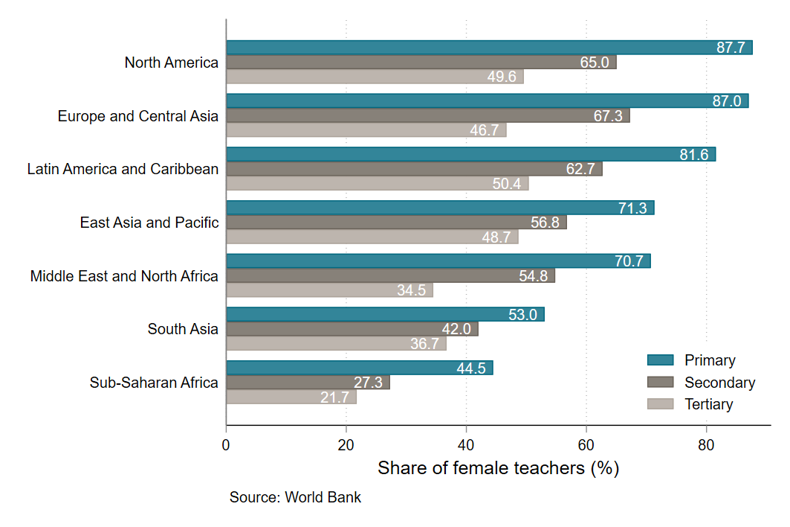

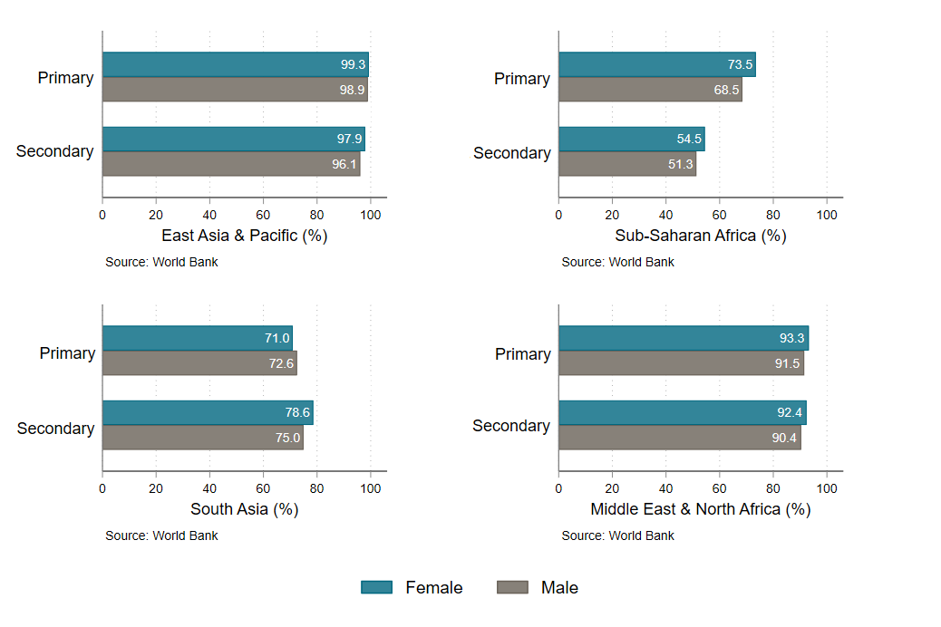

3. Female teachers tend to teach lower grades

Almost universally, there are more female teachers at lower grades. Across all regions of the world, income levels, and time spans, there are more female teachers at primary level than secondary level and more at secondary level than tertiary level. Out 150 with available data, we found just four with a higher share of female teachers in secondary than primary (Bhutan,Myanmar, Côte d’Ivoire and Pakistan with a small difference of –5 points) and one where there are more female teachers at tertiary level than secondary level (Bangladesh, 2 points difference). The rest follow the pattern (see Figure 4).

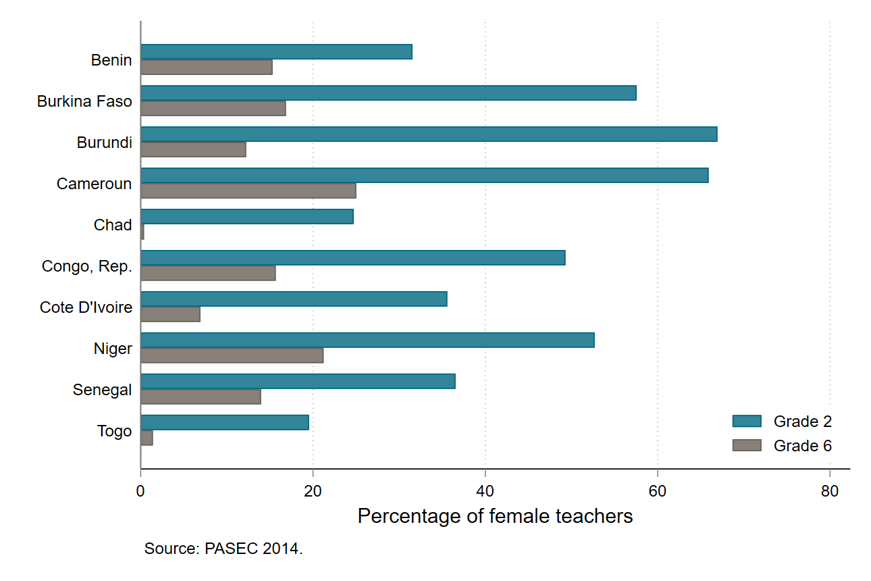

And within the general categories of primary, secondary, and tertiary, female teachers are more likely to teach earlier grades. Figure 5 shows at least twice as many female teachers in grade two than in grade six. In Togo and Chad, there are barely any female teachers in grade six.

Is there a good reason for this? It is not clear that there is evidence that female teachers are more effective at teaching low grades than men. We know that the gender of a teacher can matter for girls’ achievements and aspirations, and limited evidence suggests that positive impacts may be greater in middle schools. Reallocating female teachers to teach higher grades may be an important way to support girls’ education.

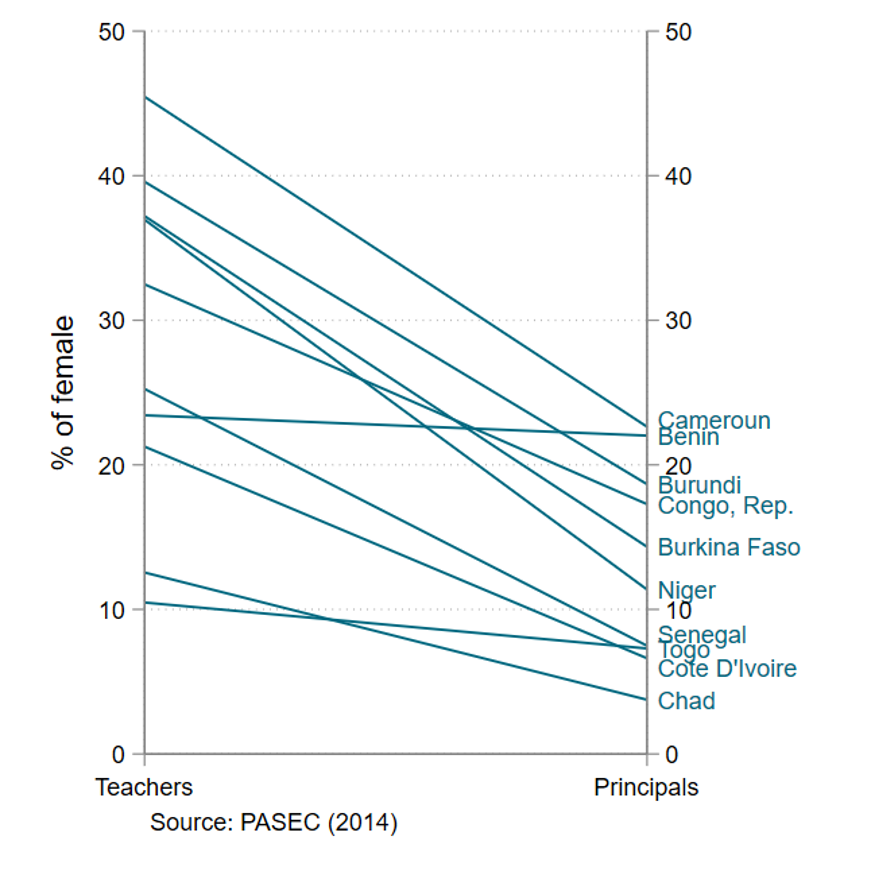

4. There is a glass ceiling for female teachers

Women are under-represented in leadership positions in schools, a pattern that seems to be common across most countries and income groups. A survey of 28 OECD countries found that women make up 70 percent of lower secondary teachers but only 45 percent of school principals. The pattern is similar across developing countries: in Sri Lanka, 71 percent of teachers are female but only 28 percent of principals are (Kelleher et al., 2011).

5. Setting the record straight on female teachers

If anyone ever thought that female teachers are less qualified than men, they should look at the data. We find that female teachers are just as qualified as male teachers.

As for the notion that women may be more likely to quit teaching jobs than men (notably to look after their own children), we find that, in 31 out of 45 countries with available data, teacher attrition rate is actually lower for women than for men.

6. Teaching makes up an important share of qualified jobs in poor countries for women

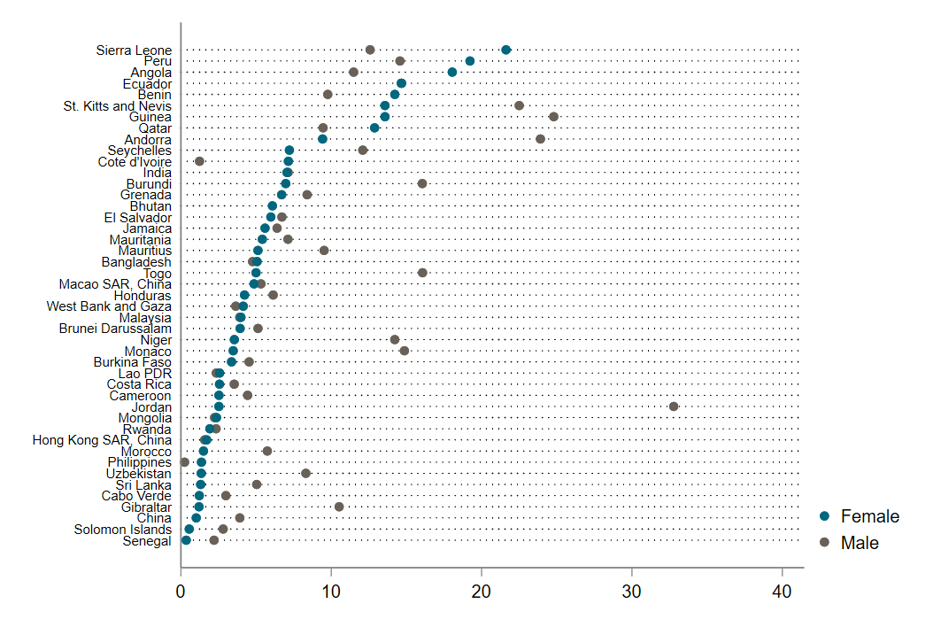

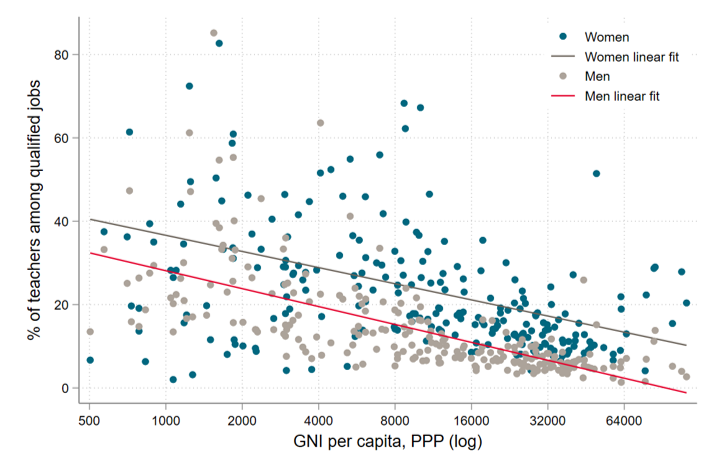

Female teachers are important for education systems, but the reverse is also true: teaching is important for women. Indeed, in very poor countries teaching is one of the few high skilled, or qualified, jobs that women can access (meaning jobs categorized by the International Labour Organization as skill level 3 or 4 in its four-tier classification system).

Figure 9 shows the number of teaching jobs as a share of the number of high skilled jobs for men and women. In the poorest countries in the world, more than 40 percent of female qualified jobs are teachers. The share decreases as countries get richer and there are more and more qualified jobs available but teaching still makes up 20 percent of qualified jobs for women at countries with a purchasing power-adjusted GNI of $16,000—twice the percentage of qualified jobs for men.

Recruitment policies of Ministries of Education therefore likely matter a lot for women. Recruiting more women as teachers can be a way for governments to boost the number of women who hold qualified jobs and promote gender equality.

Concluding remarks

Female teachers already make up the majority of teachers in the world, and we can expect that their share will continue to rise—but Ministries of Education should still think carefully about the management of their female teachers. Getting more female teachers in rural or remote areas is challenging but might be desirable to offer job opportunities for women in these areas and give female students a chance to have a teacher that looks more like them. There is nothing wrong with women predominantly teaching early grades, but it is not obvious that it is always where female teachers would perform better, and older students may also benefit from having a female teacher. Finally, education systems need to make sure that barriers are not created for female teachers and that women have the same chance as men in being promoted to managerial positions.

Disclaimer

CGD blog posts reflect the views of the authors, drawing on prior research and experience in their areas of expertise. CGD is a nonpartisan, independent organization and does not take institutional positions.