Recommended

Those of us who have spent our lives in health security and global health have watched the unfolding COVID-19 pandemic with a sense of both concern and anger. For the last decade the world has experienced over 20 epidemics and pandemics from “old enemies” such as measles, to Zika, and not one but two major outbreaks of Ebola. Already in this decade we have experienced the Middle East coronavirus outbreak caused by another “novel Coronavirus.” But the lessons these pandemics have taught appear to have been ignored. As governments proceed to pursue social distancing and lockdown measures, we urgently call for the development and communication of exit plans, increased testing to inform planning, and a rethink of global supply chains of critical items such as ventilation equipment.

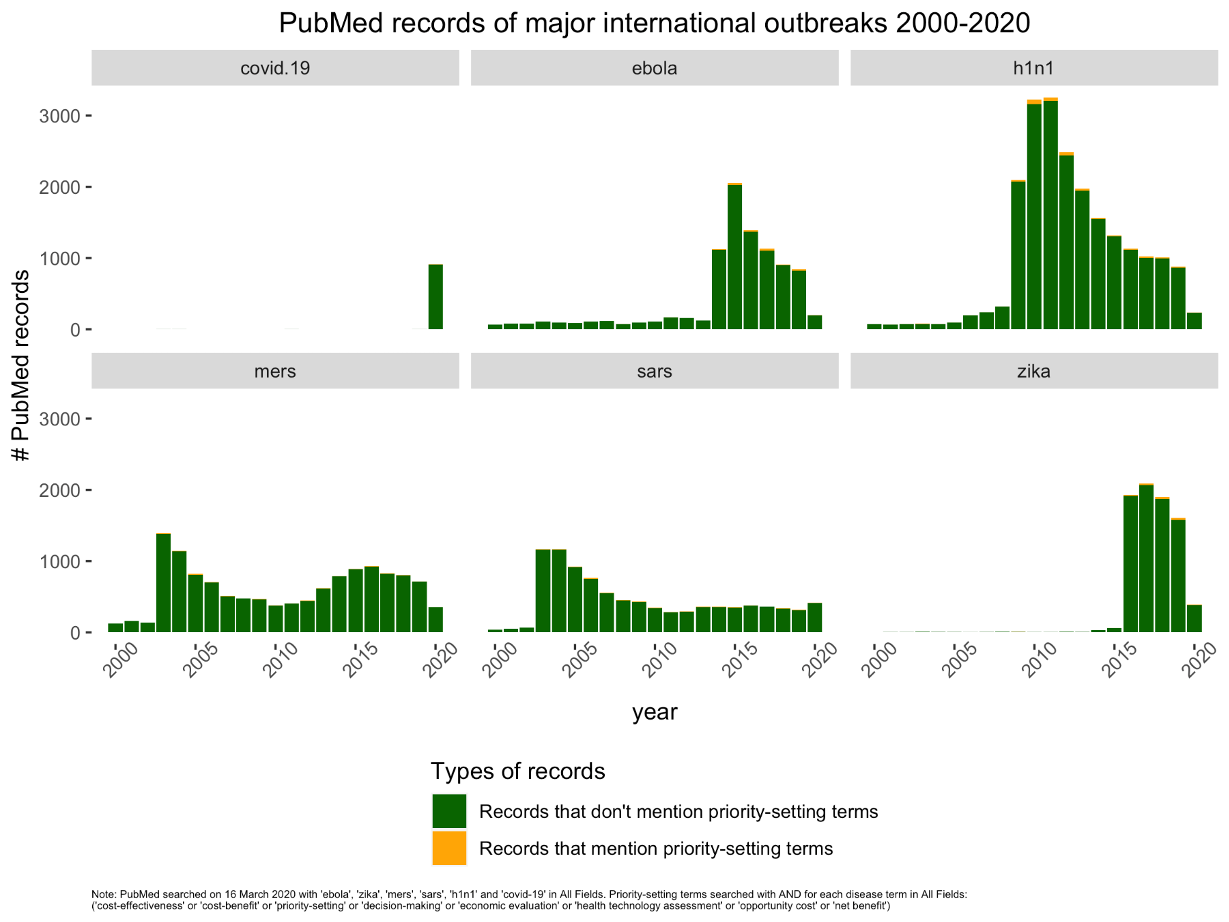

Learning from previous outbreaks

Building on the outbreaks of the past 20 years, there was much to learn; that ground data on disease prevalence (and population immunity) is key, that indirect consequences of massive social isolation/lockdowns must be integrated into policy decisions, and that health systems need to be able to cope with surge demand. Those countries—China, Singapore, South Korea, Germany—that have reached some degree of control around hospitalizations/ITU have done so through testing at scale, tracing, and isolation, using–in some cases–the full spectrum of their security sector. Other countries have temporarily delayed COVID-19 because of their geographical isolation and border closures. Most countries, particularly in the low- and middle-income group, have no system capacity to react to COVID-19 either to test/trace or to care for hospitalised patients (especially on intensive care). Why have we not managed to employ the key lessons from these previous outbreaks?

These will also have deep and lasting consequences for our social fabric particularly for older people and vulnerable and marginalized groups, the very people they are supposed to protect. Social abandonment is already happening in both life and death.

The current policy response

We are now witnessing a convergence in national responses with aggressive social distancing and isolation measures “to flatten the curve” to a large extent driven by clinical impact and political optics of COVID-19 surges into underprepared and under provisioned health systems. The unintended health and economic consequences of these measures—which in some settings may lead to more harm than good—seem to have played a limited part in policy calculations, and were explicitly excluded from modelling analyses informing public policy. Lockdowns may currently be needed to prevent overwhelming hospital and ITU capacity in some systems but their utility in many places where social mobility is a matter of day to day survival is very questionable. These will also have deep and lasting consequences for our social fabric particularly for older people and vulnerable and marginalized groups, the very people they are supposed to protect. Social abandonment is already happening in both life and death. Isolation is leaving vulnerable groups disconnected from social support and care with some shocking consequences, as dying patients are “barriered” away in their last hours from loved ones. At the same time and as care services are focusing on keeping people out of the hospital and re-orientating to current and (possible) future surges in COVID-19 hospitalizations, access and treatment across the disease continuum from cancer to elective surgery are all being scaled back with significant consequences (here, here and here). In some countries, the lockdown measures have been so draconian, that they have essentially meant that many are “locked out” from healthcare. This is likely to lead to significant downstream mortality and morbidity form cancer to mental health.

Urgent call for an exit plan

Lockdown has been as much about the political optics of unmanageable patient admissions as it has been about public health. The reality is that COVID-19 is here to stay. It has evolved the perfect set of attributes to do this. Highly infectious, globally distributed, a large population reservoir with only mild symptoms and low infection fatality rate (best estimates show this is below 1 percent for COVID-19). Barring a sudden change in pathogenesis of SARS-CoV-2 (the virus that causes COVID-19 disease) with seasonal waning of the pandemic and/or a safe and effective vaccine, this new coronavirus will continue to circulate and re-infect populations. Are we to expect lockdown indefinitely? There is no consideration of an exit strategy. The notion touted of “wait and see” and lockdown measures being intermittently lifted and then re-imposed is economic and social suicide.

Unintended consequences

While these consequences are already being realized in many countries, the knock-on effects on the global economy will devastate billions of people already struggling to survive in poor and emerging economies. In many parts of the world social distancing and lockdown policies could have even more disastrous consequences that go beyond just health outcomes, including stability and security. According to the World Bank, across East Asia and Pacific, 24 million fewer people will escape poverty in 2020. In their latest report, the economic commission for Africa estimates that “Africa may lose half of its GDP” with food and drug shortages, capital flight, slowdown in investments, and record levels of unemployment: all this before COVID 19 spreads across the continent. With GDP per capita reductions directly linked to dramatic increases in infant mortality (especially for girls), the poorest and most vulnerable are likely to be hit the hardest. In the lockdown of India the impact, if fully felt, will kill far more from indirect consequences than from COVID 19.

Lockdown has been as much about the political optics of unmanageable patient admissions as it has been about public health. The reality is that COVID-19 is here to stay. It has evolved the perfect set of attributes to do this.

WHO’s guidance and national responses

From the very beginning the WHO have been pleading to test, trace, and isolate, as well as scale up system capacity and capability for care. The abysmal failure to heed this advice (especially in relation to testing) has led countries like the UK into the cul de sac of national lockdown and catch-up to source more testing capacity and healthcare equipment. The lack of testing has also meant large number of healthcare professionals being unable to work as they self-isolate because of their symptoms or those of family members. In addition the failure to procure and distribute required Personal Protective Equipment (PPE) as well as mechanical ventilation equipment has essentially capped the NHS ability to manage any sort of surge as well as a serious drop in professional trust in the government's handling of this crisis. The saving grace being the professionalism of leadership and organization by many individual hospitals and healthcare staff.

Recommendations and Policy Changes

- Rapid scale up of testing for SARS-CoV-2 (the virus that causes the COVID-19 disease) and antibodies to symptomatic population and healthcare workers.

- Re-evaluation of communication strategy.

- Total rethink of critical planning for pandemics especially sourcing and logistics chains for mission critical equipment from PPE to mechanical ventilation, et al.

- The development of an urgent exit plan that explicitly takes into account the social and economic consequences of policies predicated on serious social distancing/national lockdowns.

The COVID-19 pandemic has exposed the inherent vulnerabilities of globalization: that health system capacity is unequally distributed, with unequal ability to deal with the global spread of disease that comes with widespread movement of people. It has–as if we needed to be reminded–exposed fundamental weaknesses in our health systems related to disease surveillance/laboratory medicine, healthcare capacity, and the political choices underpinning all of this. It has also shown a massive gap between evidence generation and policy with the failure to include wider social, economic, and clinical consequences of public health actions. The temptation will be to try and sweep this under the carpet. This would be a colossal mistake. The next disease we don’t yet know about may spread like COVID-19 but exact a 50 percent case fatality rate. The consequences of that, to borrow an English colloquialism, will make the COVID-19 pandemic look like a Sunday holiday.

Disclaimer

CGD blog posts reflect the views of the authors, drawing on prior research and experience in their areas of expertise. CGD is a nonpartisan, independent organization and does not take institutional positions.

Image credit for social media/web: thodonal via Adobe Stock