Recommended

POLICY PAPERS

In recent years, the international constituency for development has expanded beyond the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development's (OECD) Development Assistance Committee (DAC). At a time when the global nature of development challenges requires utilizing diverse skills, knowledge, and resources, this expansion brings new opportunities for cross-actor learning and cooperation to advance the shared 2030 Agenda. Yet challenges to such cooperation remain: the rapidly changing landscape and heterogeneity of non-DAC providers makes it difficult to understand which non-DAC countries now provide cooperation, what they do, and how open they are to partnerships with other providers.

In this blog, we summarize findings from a new paper that maps the landscape of 54 non-DAC cooperation providers and how they cooperate for development. We identify the range of countries with agencies for providing cooperation, how much they provide, and where and on what it is spent, and a series of case studies explore how these features changed over time in five countries. We then develop a novel framework to capture differences in non-DAC provider willingness and ability to partner with other cooperation providers on development issues.Our results show that while most non-DAC providers are at least somewhat open to multi-provider partnerships, there remain important questions about how to turn this engagement into deeper collaboration for development.

Which non-DAC countries have institutionalized outward cooperation, how much do they give, and where does it go?

We begin by identifying the breadth of non-DAC countries that currently provide development cooperation, ultimately including 54 non-DAC cooperation providers with institutions responsible for managing outward— or “dual”—cooperation as part of our sample. These providers include countries from all income groups and regions (a full list of countries and agencies is available in Annex 1 of our study).

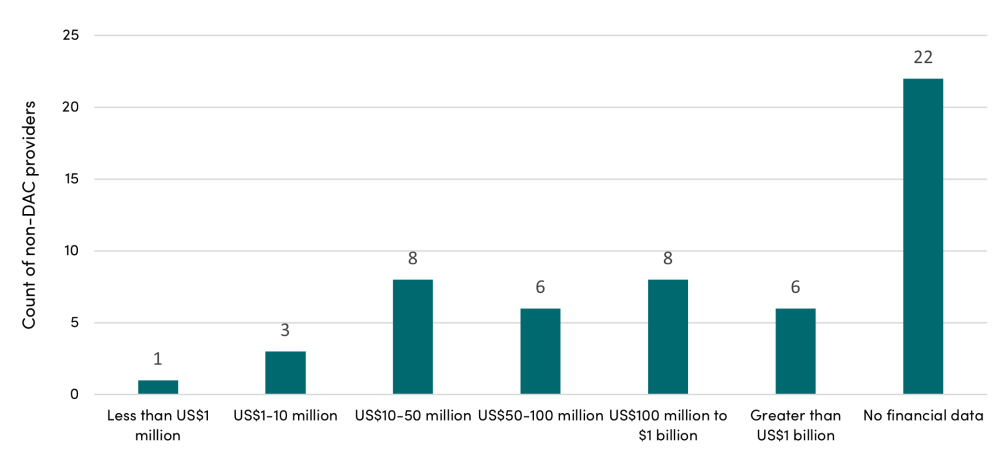

Of the providers included in our sample, financial cooperation data available shows that six non-DAC providers—China, India, Russia, Saudi Arabia, Türkiye, United Arab Emirates—allocated more than US$1 billion in cooperation in the latest year for which data is available, the bulk of which was allocated bilaterally (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Histogram of non-DAC provider countries by annual volume of cooperation

Source: Data compiled from a combination of OECD and country-reporting sources. In all cases, data reflects the latest year for which information is available.

While limited disaggregated data makes it difficult to precisely identify the modalities, sectors, and regions of cooperation, we conducted a qualitative review of non-DAC provider agency websites and documents to draw-out broad trends in how non-DACs cooperate. Unsurprisingly, our review showed that most non-DAC providers offer technical exchanges in a diverse range of sectors based on domestic expertise. We do, however, see differences in the cooperation offered by providers at different levels of income, with higher-income providers (including non-DAC European countries and providers from Gulf states) or large economic powers (namely China, India, Russia) utilizing financial cooperation modalities alongside technical exchanges. Similarly, higher-income providers identify cross-cutting cooperation priorities—notably environmental protection or climate action—as part of their cooperation offer more frequently than middle-income providers, which tend to prioritize social, and productive sectors more strongly.

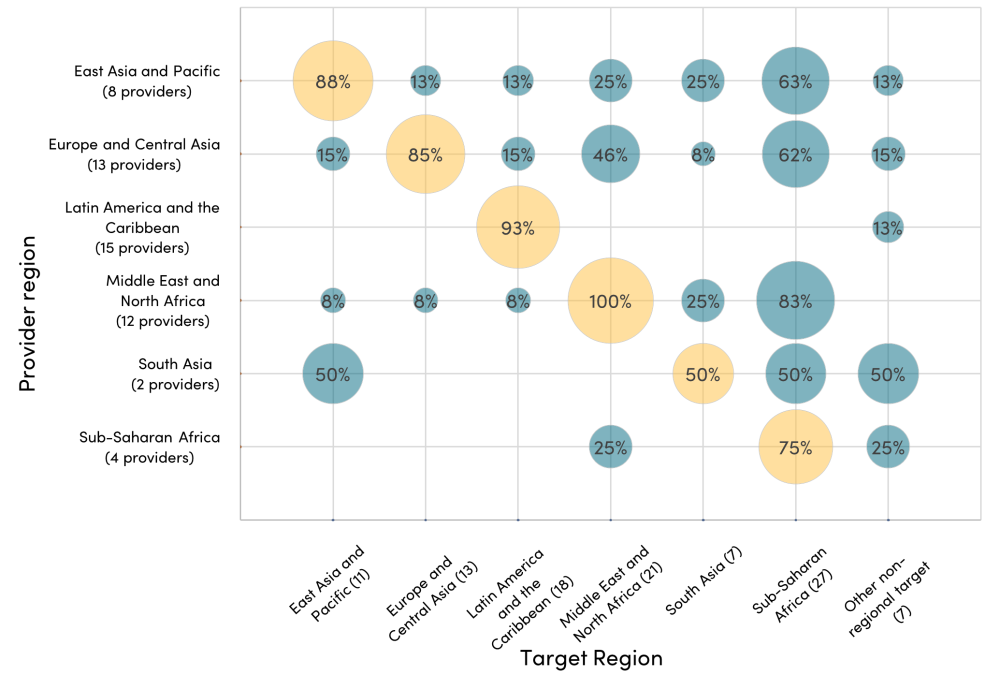

As part of this review, we also mapped priority regions listed by non-DAC providers to understand where their cooperation flows. Our review showed that most non-DAC providers prioritize cooperation with countries in their region (see Figure 2), with higher-income countries appearing more likely to prioritize regions beyond their neighbourhood. The prioritization of cooperation in providers’ immediate region is unsurprising due to both the efficiencies of working close to home and the mutual benefit of promoting regional development. Overall, however, sub-Saharan Africa was the region most frequently targeted, with half of the providers in our sample identifying it as a target for cooperation.

Figure 2. Share of non-DAC providers, by region, identifying other regions as a priority

Source: Authors’ analysis based on data from OECD and non-DAC provider sources.

How open are non-DAC providers to multi-actor partnerships for development?

As a first step towards thinking about the barriers and opportunities for deeper cross-provider partnerships for development, we sought to understand how—and to what degree—non-DAC providers currently participate in cross-actor partnerships for development dialogue, reporting, and action. To do so, we developed a simple composite indicator that maps provider openness to multi-partner engagement as a function of (1) participation in international development forums at both the OECD and UN, (2) reporting development cooperation spending to international repositories, (3) participation in triangular cooperation, and (4) voluntary contributions to multilateral or regional development bodies measured out of a possible four points. We then map this openness measure (on the x-axis) against providers’ relative capacity for cooperation, proxied by GNI per capita (y-axis), to create a dynamic scatterplot for visualizing differences in non-DAC engagement in key multi-actor partnerships (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Framework for illustrating non-DAC providers’ capacity for cooperation and openness to multi-partner engagement

Note: full details of the framework methodology and approach can be found in our paper (p.49)

Overall, we find that most non-DAC providers are currently open to beyond-bilateral partnerships for development, with 32 of the 54 non-DAC providers scoring at least two of the four possible points for openness. Our mapping also reveals four main categories of non-DAC providers situated within the four quadrants of the resulting scatterplot. While our framework shows similarities across providers from the same region - suggesting that shared histories and geographies affect how and to what degree non-DAC providers will cooperate with others—this model allows for recognising intra-regional variation as well as noting potential commonalities between providers with different backgrounds.

- Higher-income, high-openness providers actively participate in shared development forums and, in theory, have the financial resources to engage in a diverse array of cooperation activities and types of partnerships for development. This quadrant notably includes all of the Gulf providers, that engage in forums for development dialogue, contribute to multilateral and regional development institutions, and report cooperation flows to international repositories.

- Lower-income, high-openness providers include countries that are active in international spaces for development yet may have fewer financial or human resources available to dedicate to deepening partnerships for development cooperation. This densely populated quadrant sees a strong showing of Latin American providers, alongside counterparts from Central Asia and the Caucasus (Kazakhstan and Azerbaijan), North Africa (Morocco, Tunisia and Egypt), and Southeast Asia (Indonesia and Thailand), as well as South Africa and Türkiye.

- Lower-income, lower-openness providers may be more likely to engage in development cooperation chiefly through bilateral channels, rather than through shared forums or modalities. While the countries that place in this quadrant are regionally, politically, and economically diverse, many are united in facing domestic challenges contributing to institutional or social fragility (including Comoros, Iraq, Palestine, and Venezuela), or by their lower democratic qualities (including China, Cuba, Vietnam, and Russia).

- Higher-income, low-openness providers include those which, in theory, have higher capacities to provide cooperation, but choose to engage with other providers more selectively via specific cooperation forums. This group primarily includes EU member countries that have not joined the OECD-DAC (Croatia, Malta, and Cyprus, as well as Latvia and Estonia placing on the line), non-EU European city-states (Andorra, Monaco, and Liechtenstein), and two of the less populous but relatively prosperous East Asian providers (Singapore and Taiwan).

Towards deeper partnerships for development

The diverse array of cooperation providers participating in the development landscape means that here are greater opportunities for multidirectional learning and partnerships to improve development impact. But are the current forums for shared action and dialogue are fostering spaces for meaningful exchange and partnership? While our forthcoming work will aim to probe this question more deeply, this paper provides a starting place for not only understanding broad trends in cooperation from non-DAC providers, but how they currently engage in cooperation for development.

Disclaimer

CGD blog posts reflect the views of the authors, drawing on prior research and experience in their areas of expertise. CGD is a nonpartisan, independent organization and does not take institutional positions.

Image credit for social media/web: Adobe Stock