Recommended

Introduction

We are living in a time when many countries face heightened debt vulnerabilities. Already high before the pandemic, debt levels reached a 50-year peak following the growth in government spending to combat COVID-19. Debt is not inherently bad; borrowing can allow countries to finance vital government investment. But unsustainable levels of debt can have devastating consequences for a country’s population, crowding out government spending on even basic necessities including food, medicine, and fuel imports. In Sri Lanka, for example, 71 percent of government revenue was spent on debt service before the country defaulted. Even where the tradeoff is not so dire, unsustainable debt service can limit productive investments in infrastructure, education, healthcare, and other sectors, hampering the economic growth necessary to reduce a country’s debt burden.

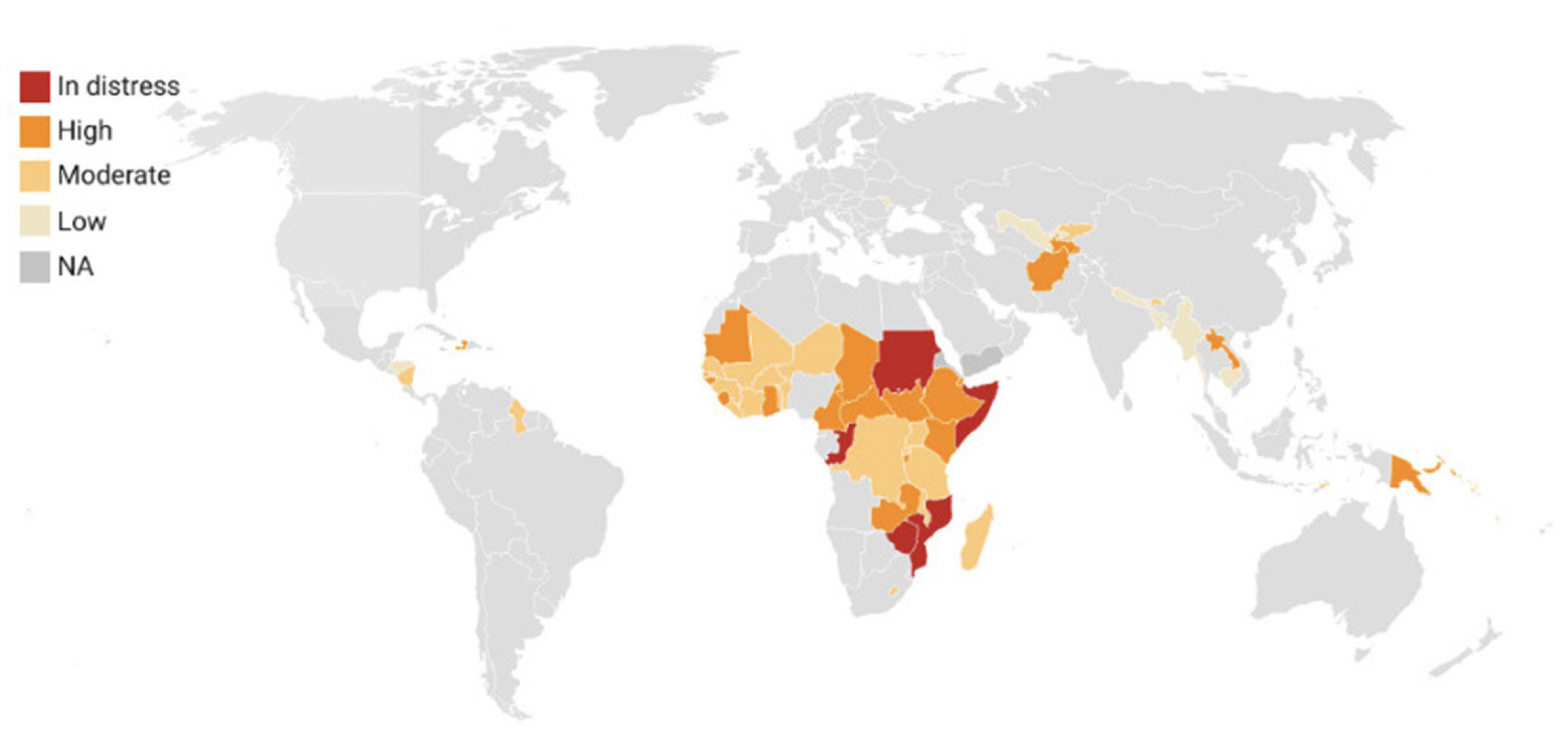

After a decade-long period of low borrowing costs, a confluence of rising interest rates, inflation, and commodity shocks have raised the likelihood of overlapping debt crises in developing countries. The International Monetary Fund (IMF) now estimates that 30 percent of emerging market countries and 60 percent of low-income countries could face trouble paying down their debts or will soon.

There is no international bankruptcy mechanism for countries that default on their external obligations. Instead, countries have historically depended on a patchwork of precedents, contracts, and conventions to bring creditors to the table for debt relief negotiations. The United States has a legacy as the lead architect of large global debt relief initiatives, from the Brady Bond plan for Latin America to the Heavily Indebted Poor Countries (HIPC) Initiative that kickstarted debt relief for poor countries in the 1990s. However, the global creditor landscape has changed significantly over the past decade. Low-income sovereigns’ largest creditors today—China and private bondholders—operate under much different principles than the leading bilateral creditors of the past, making the traditional norms and structures less effective for present debt challenges. The objective of the international financial architecture—historically overseen by the IMF and its shareholders— will be to corral these new creditors into a cooperative arrangement to deliver on debt relief.

Key terms

Sovereign debt: The money that a sovereign nation (country) owes to its creditors, including both principal (the money borrowed) and interest (the cost of borrowing)

Debt service: The money needed to pay the principal and interest of an outstanding debt over a given period

Debt distress: When a sovereign has trouble servicing its debt

Sovereign default: When a government stops paying its debt service, usually followed by a credit rating downgrade and loss of access to additional borrowing

Debt restructuring: Changing the terms of sovereign debt to make paying debt service more manageable (can involve changing maturities, adding grace periods, reducing the principal amount of the debt, reducing the interest rate, debt service suspension, etc.)

Figure 1. Debt distress level, by LIC

Sovereign debt restructuring actors

Sovereign debt restructuring is complex, involving the national government, international creditors, and various third parties, principally the IMF.

The sovereign debtor is the country pursuing or in need of debt relief. It includes not just the central government, but also state-owned or state-backed entities whose debts are guaranteed by the government.

The creditors are any entities that have lent to a sovereign. For low-income countries, these have generally comprised three broad categories:

- Multilateral creditors are typically international financial institutions (IFIs) including the World Bank, regional development banks, and the IMF. These creditors generally lend money on concessional terms, meaning that sovereigns pay less interest and have longer repayment periods than they would if borrowing from the private sector.

- Commercial creditors include commercial financial institutions and bondholders (which may be individuals, institutional investors, or other sovereigns). They lend to governments at the prevailing market rates.

- Bilateral creditors are government lenders including the United States and most OECD countries (some of whom are members of the Paris Club, see box) along with emerging lenders like China.

What is the Paris Club?

The Paris Club is an informal group of creditor countries whose objective is to find sustainable solutions to sovereign debt payment difficulties. It has historically held much of emerging countries’ sovereign debt, and operates according to six foundational principles:

- Solidarity: All members of the Paris Club agree to act as a group in their dealings with a given debtor country.

- Consensus: Paris Club decisions cannot be taken without a consensus among the participating creditor countries.

- Information sharing: Members will share views and data on their claims on a reciprocal basis.

- Case-by-case: The Paris Club makes decisions on a case-by-case basis to tailor its action to each debtor country’s individual situation.

- Conditionality: Agreements with debtor countries will be based on IMF reform programs that help ensure the sustainability of future debt servicing.

- Comparability of treatment: A debtor country that signs an agreement with the Paris Club agrees to seek comparable terms from all bilateral creditors, including non-Paris Club commercial and official creditors.

The six shared principles of the Paris Club ease the challenges of debt restructuring negotiations, but the most important among them is comparability of treatment, given that negotiations can break down if even just one creditor appears to be getting a better deal than others. However, the cast of creditors is more diverse than it once was, and includes bondholders, state-owned enterprises, and non-Paris Club official creditors like China. These newcomers, especially China, are much more likely to negotiate the restructuring of their claims independently, in direct contrast to the principles of solidarity, consensus, information sharing, and comparability of treatment.

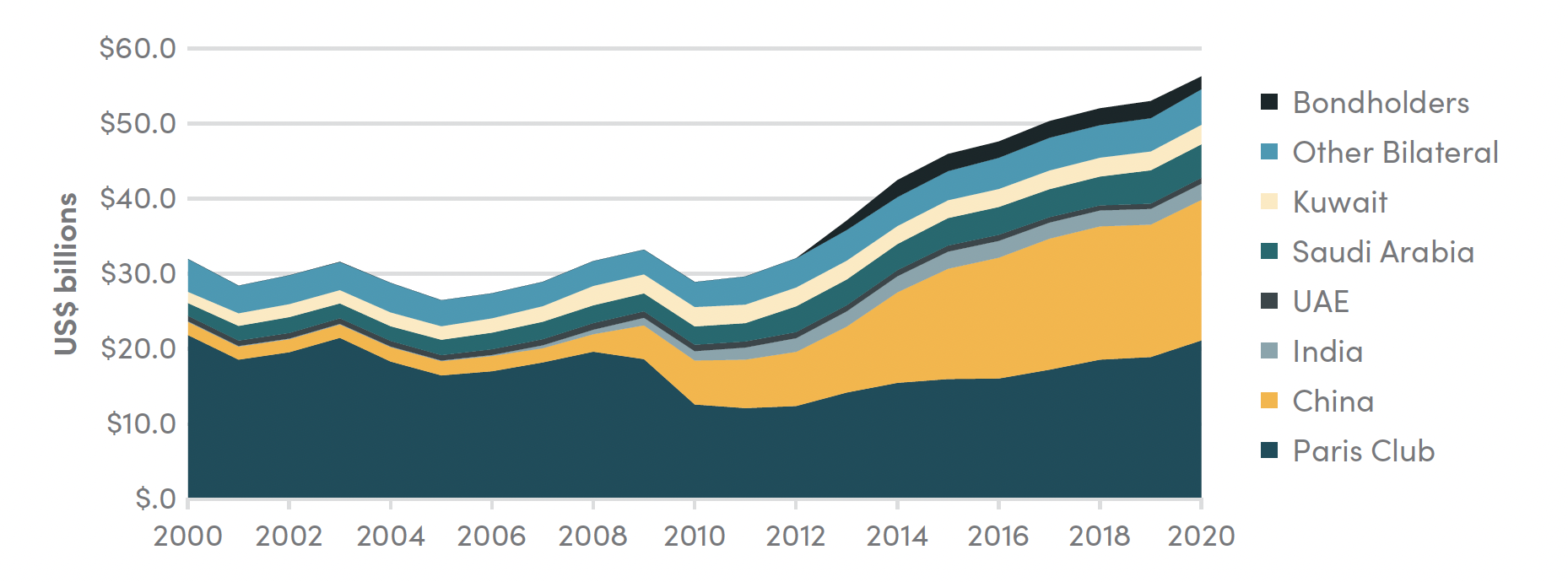

Figure 2. China's share of LICs' public external debt stocks has risen over past 20 years

Note: Excludes multilateral creditors.

Sovereign debt restructuring

Restructurings can be divided into three stages: initiation, negotiation, and application. Though they have become more efficient since the introduction of collective action clauses (CACs, described below), the nine restructuring cases between 2014 and 2020 took an average of 1.2 years. The IMF plays the role of arbiter in this process, first identifying what relief is needed through a debt sustainability analysis (DSA), and eventually providing countries with the liquidity and policy frameworks they need (alongside debt relief) to return to debt sustainability.

Initiation. To initiate the process, a country must first determine whether it can continue servicing its debt or whether a restructuring is necessary. If a country owes more than it could realistically hope to pay at any point in the future, it is insolvent, and debt restructuring is needed. But this determination, based on the findings of a DSA, is not always easy to make; and it is generally conducted with the IMF after the country has approached it for a program. If a country is deemed insolvent, the IMF will move forward with a program—but only if the government implements the IMF’s recommended policy changes to restore debt sustainability, including approaching its creditors to restructure its debts. Because these policy changes address fundamental imbalances in a country’s economy, they can be economically painful and politically challenging, which is why the IMF is both in name and practice the lender of last resort—countries generally avoid engaging with the institution until there are no alternatives.

Negotiation. Once a country commits to pursuing a restructuring, it must then negotiate a relief agreement with its creditors. The IMF DSA will have outlined the level of relief required to restore the country to sustainable levels. The challenge for the government is then to negotiate the level and modalities of relief required from each creditor, which often requires securing participation from its creditors on comparable terms. The parties have three main tools at their disposal to achieve the necessary debt relief in a way that still satisfies creditors: changing maturities (the date on which final payment is due) and/or grace periods, reducing the principal amount of the debt, and/or reducing the interest rate. Most debt restructurings use a mix of these tools to achieve the necessary relief.

Application. After negotiations on the terms of debt relief conclude, a country must maximize creditor participation and apply comparable treatment to all creditors to successfully close out a restructuring. This effort can be hampered by “holdout” creditors that avoid making any concessions to collect payment in full once other parties have provided relief (freeing up the money needed to pay back the holdout creditor). In the case of bonds, this holdout behavior is disincentivized by collective action clauses (CACs), provisions that allow a majority of bondholders to bind the minority to the terms of a restructuring through voting. CACs are only a feature of bonds—bilateral loans (both commercial and official), syndicated loans, and sub-sovereign borrowings generally do not include these features, meaning that holdout creditors are still a significant risk to successful restructuring.

Restructuring success story: Mexico’s Brady Bonds

After a period of strong growth for Mexico, the oil shock of 1979 ushered in a global recession that hit the country hard, leading to a decline in non-oil exports and rapid devaluation of the peso. These factors made the country’s already-large external debt more expensive to service. By 1982, with the country’s debt service far greater than its monthly foreign exchange income, Mexico was on the verge of default.

The first response from creditors (mostly commercial US banks) was to suspend debt service for two years and extend new loans to Mexico. The hope was that with renewed foreign exchange liquidity and an IMF adjustment program, the country would be able to grow into its debt. Instead, however, capital outflows and inflation continued, and investment withered, resulting in stagnant growth and an increase in external debt.

By 1989, it was clear that greater action was needed, and the “Brady Plan” was initiated – named for the US Treasury Secretary who proposed the initiative. The plan offered creditors three choices to restructure the outstanding debt: reduce principal, reduce interest, or maintain both and provide new loans. Most creditors opted for the first two options, and the reduced debt service burden on the country combined with economic reforms helped usher in a period of improved economic growth for Mexico.

Track record of multilateral debt relief initiatives: HIPC and MDRI

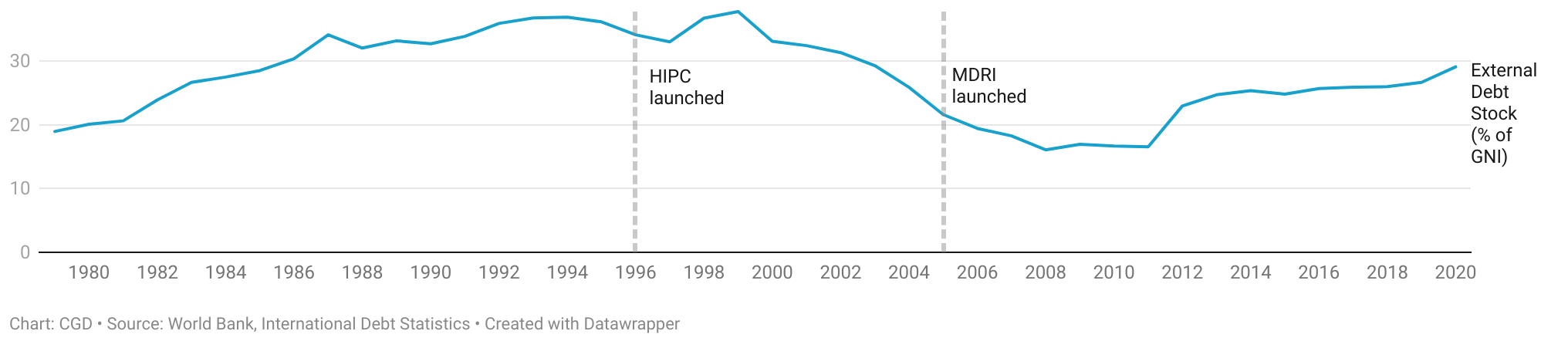

In 1996 the World Bank and the IMF—alongside other bilateral creditors, led by the US—launched the Heavily Indebted Poor Countries Initiative (HIPC). HIPC reduced the external debt of countries that met specific criteria to ensure poor countries don’t face unsustainable debt burdens. Since its establishment, the initiative has approved debt reduction packages for 37 countries, 31 of them in Africa, providing approximately $76 billion in debt-service relief in total.

Figure 3. LIC and MIC external debt stocks fell after HIPC and MDRI, but have since risen

HIPC adopted a two-step process; to reach a “decision point” a country had to fulfill certain conditions to be eligible to initiate relief, including demonstrating a track record of reform and sound policies through IMF- and World Bank-supported programs and developing a Poverty Reduction Strategy Paper (PRSP) outlining the policies and programs it would implement to promote growth and reduce poverty.

The second step or “completion point” of HIPC requires countries to implement their PRSP for at least one year, alongside key reforms established at the decision point, to receive full debt relief. Just over half of the funding for debt relief under HIPC came from bilateral creditors, including the United States, with the remaining portion supplemented by IFIs and select private creditors. Like other multilateral debt relief efforts, creditor participation in HIPC was voluntary.

Though HIPC was successful in reducing the bulk of bilateral HIPC debt, countries continued to bear the weight of servicing multilateral debt, leading the G8 finance ministers to establish the Multilateral Debt Relief Initiative (MDRI) in 2005. The debt relief program aimed to reduce 100 percent of the claims of the IMF, the World Bank’s International Development Association (IDA), and the African Development Bank (AfDB), and was opened to countries at or on their way to the HIPC “completion point” (though relief from the IMF was later opened to both HIPC and non-HIPC countries). For the countries who qualified, the MDRI succeeded in drastically reducing multilateral debt, but not without costs to creditor countries—donors agreed to compensate the IFIs on a dollar-for-dollar basis for the foregone reflows associated with the relief. For instance, the United States promised annual payments to the African Development Fund (AfDF) due through 2054, and payments to the World Bank Group’s International Development Association (IDA) due through 2044, but in recent years has accrued considerable arrears.

Table 1. US unmet MDRI commitments to IDA and AfDF (USD millions)

The United States still has unmet MDRI commitments—which continue to increase unless Congress appropriates resources to cover amounts that come due annually.

|

Institution |

FY18 Enacted |

FY19 Enacted |

FY20 Enacted |

FY21 Enacted |

FY22 Estimate* |

FY23 Projected* |

|

IDA |

$820 |

$1010 |

$1240 |

$1500 |

$1800 |

$2100 |

|

AfDF |

$130 |

$160 |

$160 |

$170 |

$200 |

$230 |

* FY 2022 column reflects unmet commitments after amounts appropriated by Congress in the Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2022. The FY23 column reflects a March 2022 projection from the US Treasury’s International Programs Congressional Budget Justification for FY 2023.

Debt relief efforts since COVID-19

The global community mounted two key initiatives in response to the COVID-19 crisis, to limit the risk of defaults and allow country governments fiscal space to spend on both the health and socioeconomic dimensions of pandemic response.

The Debt Service Suspension Initiative (DSSI), endorsed by G20 finance ministers and the World Bank’s Development Committee in April 2020, was intended to provide liquidity to countries early in the pandemic. DSSI postponed debt payments from the world’s poorest countries to G20 bilateral creditors, if requested by country governments. Under the initiative, 48 of 73 eligible low- and lower-middle-income countries postponed debt payments to G20 bilateral creditors until DSSI expired at the end of 2021, ultimately suspending $12.9 billion in debt-service payments. Private creditor participation in DSSI was voluntary, and G20 countries urged private actors to seek participation on equal terms—but almost no private creditors engaged with the mechanism. DSSI was supported by the World Bank and the IMF, which advised on debt management and transparency practices and monitored public spending for participating countries. Coupling debt payment suspension with this technical assistance was crucial because countries that participated in DSSI are ultimately still responsible for paying the total principal and interest on their debt—the initiative just extended the contractual time horizon for doing so.

China as an emerging creditor

In the past decade, China has risen in prominence as a major creditor, even briefly overtaking the Paris Club in its share of outstanding public external debt of low-income countries (LICs) in 2017. This poses challenges to the traditional debt restructuring process. An analysis of 100 Chinese debt contracts found that:

- Chinese debt contracts contain unusual confidentiality clauses that prevent borrowers from revealing the terms or sheer existence of the debt

- Chinese lenders seek advantage over other creditors by using collateral agreements to keep their debt out of collective restructuring (in other words, preempting Paris Club efforts)

- Many Chinese debt contracts contain cancellation, acceleration, and stabilization clauses which, respectively, allow the lender to demand payment immediately, accelerate payment, and limit the debt’s exposure to legal/regulatory changes

These features run counter to many of the principles of the Paris Club, most notably solidarity, consensus, information sharing, and comparability of treatment. China has resisted calls for increased sovereign debt transparency through the IFIs and is reluctant to set precedents for debt forgiveness. But China’s share of LIC external debt is too big to ignore. This means that any future restructuring efforts cannot count on the scale of major creditor consensus achieved in previous debt relief measures.

In November 2020, the G20 adopted a Common Framework for Debt Treatments. The Common Framework is a partnership between the G20 and the Paris Club that sought to restructure sovereign debt, grounded in traditional Paris Club terms (going beyond the postponement of debt payments under DSSI). This framework allows creditor countries to negotiate together with DSSI-eligible debtor countries on debt treatment. Under the Common Framework, debt treatments are initiated by the debtor country, on a case-by-case basis, with an opportunity for private creditor participation.

But uptake of the Common Framework has been limited, with only three countries (Chad, Ethiopia, and Zambia) seeking relief—all of which have experienced slow progress with creditors thus far. Zambia only recently reached an agreement to initiate debt restructuring. Why the hold-up? Despite its name, the Common Framework lacks clear steps and timelines for bringing the parties to a debt restructuring together, and instead operates on an ad hoc basis allowing for high-stakes ambiguity and uncertainty. In addition, the effectiveness of both HIPC and the MDRI was predicated on multilateral and Paris Club lenders owning the bulk of poor countries’ debt. However, in the years since, the share of HIPC debt stocks owned by private and non-Paris Club lenders, namely China, has grown significantly, complicating restructuring efforts.

These creditors do not operate on the same shared principles as the Paris Club, preferring instead to pursue closed-off discussions (in the case of China) or collect repayment through court rulings (in the case of holdout private lenders). With other creditors fearful that their concessions might help these less cooperative creditors collect in full, the entirety of the restructuring process stalls, leaving countries in a bind, with growing debt service obligations, falling reserves, and no access to additional market lending.

Sri Lanka is the most recent example of a country at risk of stalled negotiations due to the disconnect among creditors. Having defaulted in May 2022, the country must now work with its creditors and the IMF to restructure its debt and return to financial sustainability. However, China owns a reported 26 percent of the debt in question, meaning that any solution will need the country’s buy-in. Again, comparability of treatment in this context is key; comprehensive restructuring is unlikely if bondholders, or other bilateral creditors like India, feel that Chinese creditors are getting a better deal. But bringing everyone to the table is not impossible—Zambia has struck a deal that includes China, allowing for some optimism in future negotiations under the Common Framework. Moreover, while corralling diverse creditors is an exercise in patience, there are some straightforward policy measures that could improve the Common Framework’s performance going forward, including a freeze on debt service for countries seeking relief, as well as more complete and realistic assessments of the debt relief needed.

As broader discussions around the gaps in the international debt architecture continue, and more countries seek restructuring or relief, the international community is under serious pressure to quickly shore up large-scale debt relief mechanisms. To be successful, future initiatives must take recent developments into account, and balance ambition with a consciousness of the new challenges facing an already-intricate process.

Key questions and additional reading from CGD for policymakers

There are no easy answers to the challenges facing today’s sovereign debt architecture, but policymakers in the US and beyond can benefit from taking new dynamics seriously and interrogating policy options.

How did the US-led HIPC debt relief impact global poverty, and what lessons from HIPC might policymakers apply today?

- Nancy Birdsall, John Williamson, Brian Deese, 2002. Delivering on Debt Relief: From IMF Gold to a New Aid Architecture, CGD Book, Center for Global Development.

Is a new coordinated creditor group, with principles aligned with emerging creditors, possible?

- Scott Morris, 2019. HIPC with Chinese Characteristics: Why Yesterday’s Debt Relief Is the Wrong Point of Reference for Today’s Crises, CGD Blog, Center for Global Development.

Given its recently limited role in direct lending to countries, what could an ambitious US agenda on debt relief look like?

- Clemence Landers, 2020. A Plan to Address the COVID-19 Debt Crises in Poor Countries and Build a Better Sovereign Debt System, CGD Policy Brief, Center for Global Development.

How can policymakers incentivize private creditors to take part in sovereign debt restructurings?

- Nancy Lee, 2020. Restructuring Sovereign Debt to Private Creditors in Poor Countries: What’s Broken? CGD Note, Center for Global Development.

What changes can be made to the Common Framework for it to move at a faster pace?

- Masood Ahmed, Hannah Brown, 2022. Fix the Common Framework for Debt Before It Is Too Late, CGD Blog, Center for Global Development.

What role could innovative financial instruments like state-contingent debt relief instruments, debt-for-climate swaps, and policy-based guarantees play in future sovereign debt restructurings?

- Nancy Lee, et al, 2021. Responding to the Risks of Covid Debt Distress, Roundtable Report, Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung.

- Clemence Landers, Nancy Lee, 2021. Belize’s Big Blue Debt Deal: At Last, A Scalable Model? CGD Blog, Center for Global Development.

- Clemence Landers, Rakan Aboneaaj, 2022. MDB Policy-Based Guarantees: Has Their Time Come?, CGD Note, Center for Global Development.

The authors are grateful to Erin Collinson, Scott Morris, and Mark Plant for their comments and suggestions on an earlier draft.

Rights & Permissions

You may use and disseminate CGD’s publications under these conditions.